The Second Karabakh War and the new geopolitics in the South Caucasus

By Abel Riu

29/01/2021

2020 is gone, but it has been a year that set global dynamics in fast motion. The tectonic plates of a changing international order have continued to move, giving rise to the emergence of new conflicts and the reactivation of old, unresolved disputes, until recently, wrongly labeled as “frozen” by some analysts. This is the case of Nagorno-Karabakh.

One of the tectonic plates that has moved more abruptly has been the Turkish one. Its diplomatic hyperactivity, and the fact that it hasn’t been shy about showing military muscle abroad, has caused plenty of headaches in Western countries. Syria and the Eastern Mediterranean have been Ankara’s main areas of power projection, where it seeks to modify the previous status quo as a fait accompli by threat or use of force.

It is precisely in the South Caucasus that this way of acting has proved most effective. Turkey’s entry into the Karabakh theatre – with direct military involvement in Azerbaijan’s military offensive in September – was decisive in blowing up the status quo resulting from the previous war between Armenians and Azeris (1991-1994) for the control of the disputed territory.

Thus, 44 days of war were sufficient for the Azerbaijani troops to impose themselves over the Armenian forces. Turkish involvement has proven crucial. Thanks to the Turkish built Bayraktar TB2 drones’ role, Azeris managed to achieve air supremacy. Turkish-Azeri military superiority over Armenians was so severe that only Russian diplomatic intervention prevented a total defeat and Baku’s recovery of the entire historical territory of Nagorno Karabakh.

The basis for the end of hostilities

The declaration on November 9th ending hostilities, signed by Russian President Vladimir Putin, Azeri President Ilham Aliyev, and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, laid the foundations for the new situation.

For the Armenian side, this entails significant territorial losses. Russia emerges as the guarantor of the ceasefire, with some 2,000 Russian military personnel as peacekeepers for a five-year period, automatically renewable if neither Yerevan nor Baku object.

The 5-km wide Lachin corridor – connecting the Republic of Armenia with the Karabakh territory – remains in Armenian hands but comes under Russian control. A Moscow’s aspiration since the end of the 90s war. The return of the territories adjacent to Karabakh – under Armenia’s control since 1994 – to Azeri hands, putting an end to one of the main elements that differentiated this conflict from the rest of unresolved territorial disputes in the post-Soviet space.

That was one of the most complex issues addressed in the peace negotiations led by the OSCE Minsk group: the fact that the independence forces had de facto control of a much larger territory than they claimed. The acceptance of the new situation implies that the Republic of Armenia implicitly accepts the internationally recognized borders of Azerbaijan.

2020 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict map. Source: Wikimedia Commons

As for the delicate question of the status of the part of the Karabakh region that remains in Armenian hands and under Russian guardianship, this remains unresolved and will be one of the most complex elements to address. In this regard, the current situation is reminiscent of South Ossetia before the Russian-Georgian war in 2008. While Baku offers “cultural autonomy”, although not political, for this territory, Yerevan defends that any solution must involve respect for the right to self-determination.

Other matters that remain open are the repatriation of prisoners of war, particularly important for the Armenian side, and which Moscow wishes to prioritize before addressing the troubling issue of the status of Nagorno-Karabakh. Russia is currently playing an important role in humanitarian assistance and the return of displaced Armenians, demining, and damaged buildings and infrastructure reparations. Turkeys’ presence is also being felt in the territories under Azerbaijan’s control.

The enforcement of Baku’s control in the bordering areas between Armenia and Azerbaijan has been traumatic for the Armenian population in the south of the country. In some cases, it is cutting off access to basic infrastructure. Meanwhile, Armenia has filed hundreds of complaints against Azerbaijan for war crimes in the European Court of Human Rights.

Keys, winners and losers of the new regional map

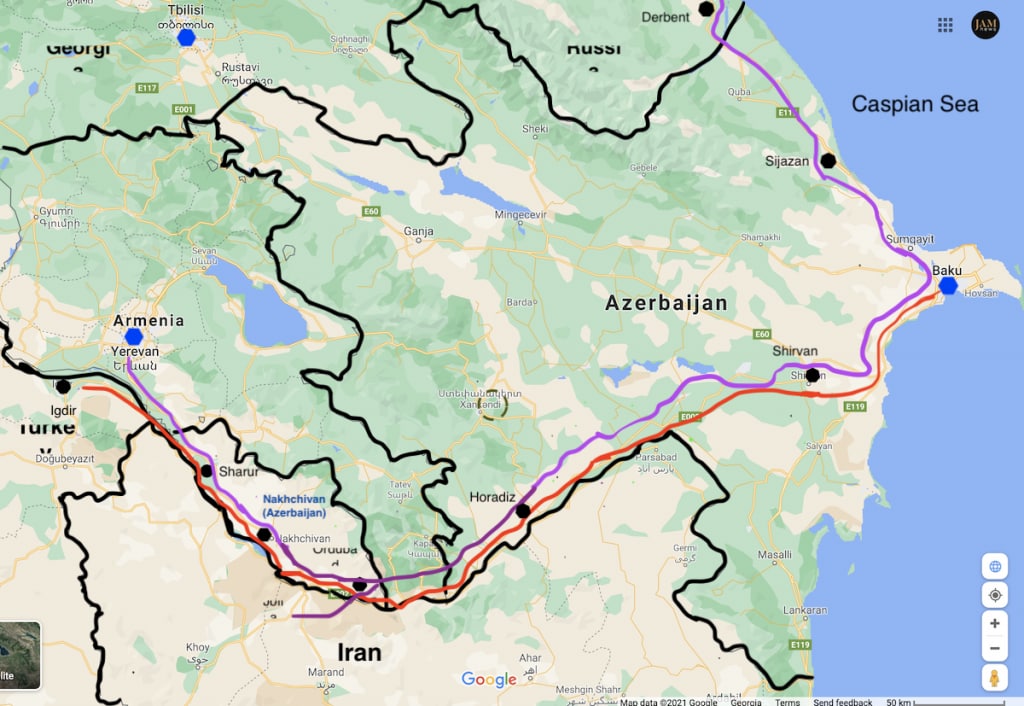

One of the most surprising points of the ceasefire agreement is that which refers to the opening of regional transport links. In its ninth and last point, the November 9th declaration states that the Republic of Armenia will ensure a safe transport corridor in the south of the country, connecting the western regions of Azerbaijan and the Azeri enclave of Nakhchivan. This corridor will remain under the Russian FSB Border Service’s control and will, in practice, connect Turkey to Azerbaijan and the Caspian Sea, avoiding Georgia’s territory.

Indeed, the meeting between Putin, Aliyev, and Pashinyan on 11 January in Moscow focused mainly on this issue: laying the foundations for the creation of new transport corridors connecting Russia-Armenia and Iran on the one hand; and Turkey-Armenia and Azerbaijan crossing Armenian and Azeri territory on the other, forming an ad hoc working group to boost work in this direction. The Russian proposal for territorial integration can be seen on this map produced by the Caucasus information medium JAM News.

Russian proposal for connectivity projects in the South Caucasus. Source: Jam News

These projects have the potential to redraw the region dramatically. To maintain control over Karabakh, Armenia paid the price of forced isolation by Baku and Ankara, with the border closed on both sides since the early 90s. All the strategic transport infrastructures built in the region over the past 20 years bypassed Armenia through its northern neighbor, Georgia. An improvement of territorial connectivity will enable Armenia to begin to overcome its regional isolation. As for Azerbaijan, it would allow it to connect with its enclave of Nakhchivan and Turkey.

Moscow would control the key to the whole workings, as the two routes (north-south and east-west) would run through the corridor in southern Armenia, guarded by the Russian FSB Border Service. This new regional reality, which is taking shape under its leadership, enables Russia to consolidate its position as the predominant and essential actor in the South Caucasus.

Through a “step-by-step” approach, Moscow is designing a new regional status quo in which it is maintaining itself as the regional boss, now with Turkey’s approval as the second power in the region and benefiting from the new situation. At the same time, by acting in this manner the Kremlin seeks to keep the EU and especially the US off the gameboard, its main concern when it comes to the areas of the former USSR where it still plays a predominant role. The new regional architecture also enables Russia to weaken the position of Georgia, the country in the area with which it has the most hostile relationship as regards to the disputes in South Ossetia and Abkhazia, and to reduce its importance as an aspiring strategic east-west cargo transport hub, also in the framework of the Chinese-led One Belt One Road initiative.

As for Turkey, thanks to its decisive role in the outcome of the war it has managed to consolidate itself as a regional co-patron, a historic novelty in the South Caucasus. Indeed, for the first time in 200 years Moscow has been forced to relinquish part of its exclusive patronage over the region, as evidenced by the fact that Turkey will from now on maintain a permanent military presence in Azerbaijani territory. Russia (and later the USSR) had enjoyed this exclusive position since the signing of the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay between the Russian and Persian empires, and the 1829 Treaty of Adrianople between the Russian and Ottoman empires, ratified a century later with the Treaty of Kars (1921) between the then nascent Turkey and the Bolshevik authorities.

As for the internal regional players, Azerbaijan is undoubtedly the great winner and dominant actor on the new stage, the logical consequence of its economic development and increased military capabilities over the past two decades, derived from the income from oil and gas exports. Its military victory and territorial conquest have almost coincided with the entry into operation in early January of the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) for supplying natural gas from the Caspian area to the EU countries. Azerbaijan’s route in Europe consists of the extension of the South Caucasus gas pipeline linking Azeri territory with Turkey via Georgia (Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum), and the construction of the Trans-Anatolian (TANAP) and Trans-Adriatic (TAP) pipelines, taking Azeri gas to the Balkans and Italy. The SGC aims above all to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian gas by diversifying imports. Promoted by the European Commission, it is a strategic project that has cost some 45 billion euros and has helped to consolidate Azerbaijan’s position as the most important state in the South Caucasus.

In this new context, Baku advocates a discourse that “the conflict is over”, and that it is necessary to focus on economic development, aspiring to become the main engine of growth that also includes and benefits Armenia. This discourse is also sometimes combined with expansionist rhetoric and claims to territories in the south of the Republic of Armenia, with racism and ethnic hatred that seek to humiliate the defeated enemy. In this respect, the rhetoric of coexistence is contrasted with that of domination, an element that does not pave the way for any possible reconciliation. Indeed, Yerevan has nowhere near the leverage it had before the war; it is much more dependent on Russia than it was before, and its position is entirely conditional on the terms that Moscow can manage to impose on Baku, and to be accepted by Turkey. It so happens that precisely the precarious situation of the Armenian side facilitates a hypothetical resolution of the conflict.

A resolution that, based on further economic integration and increased mutual dependence, could ultimately become a means for lasting peace between the two countries. This is at least the paradigm shift designed by Moscow, with the option of moving from a zero-sum game to a scenario where both sides can benefit from opportunities for greater regional socio-economic prosperity. This is a path that would by no means be easy for Nikol Pashinyan’s Armenian government, and for those who may follow, with a country in the throes of a post-defeat crisis and major internal opposition fostered particularly by the elements of the regime that governed the country until the successful revolution of 2018.

The new scenario is unsatisfactory for the United States, owing to Russia’s growing influence in both Armenia and Azerbaijan. It remains to be seen whether the new Biden administration intends to play a more active role in attempting to influence in favour of Armenian interests, as the new secretary of state Antony Blinken recently stated. This could involve using Armenia as a lever in the South Caucasus panel in the framework of the growing geopolitical rivalry between the US and Russia, attempting to reduce the influence Russia has over this country. This position is unlikely to be put into practice from the outset, as it would involve damaging its relations with Baku, which has gained importance following the opening of the Southern Gas Corridor, a project supported at the time by President Obama and with Biden as vice president.

In this sense, Washington’s movements will possibly involve reinforcing the role of the Minsk Group, without ruling out the aim of replacing the Russian intervention forces with a multinational force, which in any event would not occur until 2025 and provided it had the unlikely support of Russia. What is beyond doubt is America’s willingness to increase humanitarian support for Armenia in order to overcome the impact of the war.

For its part, the EU is another clear loser in the new scenario, unable to do anything else during the autumn war other than express “deep concern”. Its main strategic priority in the region is Caspian gas, and the Union’s relationship with Armenia and Azerbaijan has always been ambivalent, a balance which has led Brussels to turn a blind eye to the Azeri-Turkish military offensive launched in September. At the same time, the lack of direct interest in confrontation with Russia, unlike in situations such as Belarus and Georgia, has meant that incentives for greater intervention have been almost non-existent. This attitude has caused Armenian aspirations of greater involvement in the EU to plummet, and there is much disappointment not only with respect to the possibilities of a Western pivot but also with respect to the supposed values it represents of democracy and human rights. In this framework, one option for the EU in trying to play a renewed role in this conflict could be to support the investigation of war crimes and atrocities committed during the war, helping to break the cycle of impunity in relation to actions committed by Azerbaijani troops. In this respect, support for the establishment of a truth commission would be a constructive formula for recovering the lost credibility among Armenians.

Regionalisation of the conflict and a new balance of power

It may be considered that, on this occasion, if Turkey has made war possible, Russia’s role has facilitated peace. Both took advantage of an increasingly convulsed global context and the US’s de facto withdrawal from various areas of the world, ensuring the strengthening of their respective interests in the region. The regionalization of the dispute has replaced an international mediation formula (the OSCE Minsk Group) with a conflict managed in all respects by Russia; with Turkey now playing an essential balancing role.

Gerard Libaridian, a historian and adviser to the first Armenian post-independence prime minister Levon Ter-Petrosian between 1991 and 1997, recently stated that the conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis over Nagorno-Karabakh is one in which both sides “have invested their history, culture and identity”, with an approach of existential struggle that forced the rulers in power to “maintain maximalist positions in order to stay in power”. Since the end of the first war in 1994, Baku and Yerevan had conceived a possible second war as a possibly inevitable continuation of negotiations in the event of their failure, as current events show. Instead of preparing the respective populations for peace, they were preparing them for war, with militaristic rhetoric on both sides. Indeed, over the past decades both countries have been among the five states in the world with the highest military expenditure per capita (much higher total figures in the case of Azerbaijan, given the difference in GDP). Owing to their historical roots, which in the case of the Armenians’ view went back to the genocide of 1915 which was one of the world’s most serious enmities.

For the Armenians, the price to be paid for maintaining these positions has been very high, as they have not been able to take advantage of the exceptional historical circumstance of their victory in 1991-1994 to achieve a lasting peace more favorable to their interests. In the long term, this has been a fatal error due to a lack of appreciation and adaptation to the region’s changing power relations, given the increase in their rival’s demographic, economic, and military capabilities, especially since their oil export boom in 2005. Also, Armenia did not understand the implications of Turkey’s growing support for Azerbaijan, and the fact that Russia could not be counted on for Karabakh’s defense in case of attack, given the deep ties and interests that link Moscow to Baku.

Both countries are currently divided between sectors that defend maximalist positions and those with a more conciliatory approach. Therefore, although economic dependence through greater regional integration might lay the foundations for resolving the conflict, this will not be feasible without normalizing relations and ultimately reconciling between the two communities. The alternative is another war. Given the new phase of regionalization of the conflict, a third Karabakh war would most likely involve direct participation and confrontation between external actors, especially Turkey and Russia, with a much higher destructive potential than past autumn.

Abel Riu is an analyst and President of the CGI, interested in Russia and post-Soviet affairs.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the CGI or its contributors. The designations employed in this publication and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CGI concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers.