Catalonia and the fiscal deficit: a planned economic drain

28/02/2024

Some news, spectacular as it might seem, may not be relevant in its own right, but it is through the underlying reality it brings to the surface – like the proverbial finger pointing at the moon.

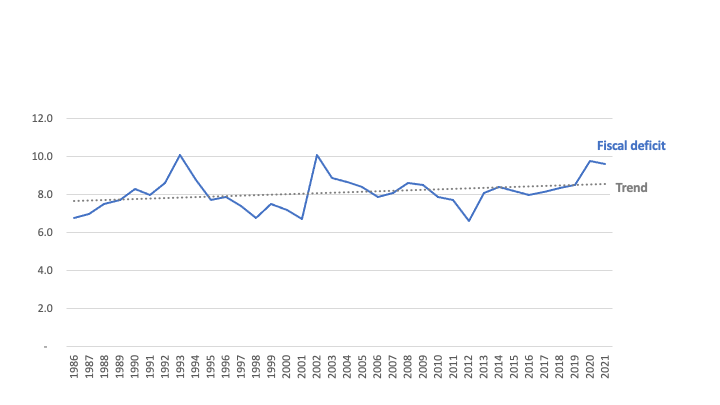

That is the case of the study that the Generalitat de Catalunya (the government of Spain’s autonomous region of Catalonia) presented last 18 September 2023, revealing that Catalonia’s fiscal deficit (i.e., the difference between the Spanish government’s revenue in Catalonia and its spending there) in 2020 and 2021 amounted to, respectively, 9.8% and 9.6% of the region’s GDP (Figure 1). In Catalonia, the news caused a gentle, somewhat despondent stir: these recent figures simply set a new high water mark for a notorious fiscal syphoning of resources that since 1986 has oscillated roughly between 7% and 10% of the region’s GDP. Despite loud and consistent outrage, this has, if anything, slowly grown over time. Elsewhere, most media did not even deem the report newsworthy: after all, the same finger comes up every year pointing at the same moon, and from the outside, it all looks just like a petty financial squabble between governments.

Figure 1: Evolution of fiscal deficit in Catalonia (% GDP – cash flow method)

Source: Generalitat de Catalunya[1] (years 2017 and 2018 extrapolated because no data from this source is available for them)

Yet the moon is still there, and it is hard to miss. Natàlia Mas, the Generalitat’s minister of Economics and Finance, described the report’s main findings as revealing “a sustained, unfair and deliberate financial strangulation ”[2] of Catalonia’s economy. Was she right? And, if so, why would Spanish governments of otherwise bitterly opposed political allegiances consistently follow such a harmful policy against one of the largest regions under their responsibility?

As always happens with politically charged debates, fiscal balance discussions in Spain are all too often stoked up around remarkably baseless objections. One of them is methodological. The approach the Generalitat uses (the “cash flow method”) is the most straightforward and intuitive: it simply computes taxes and tax-like transfers from Catalonia to Spanish government institutions, minus those institutions’ transfers and spending in Catalonia. The only major correction relates to Spain’s public debt build-up, which allows governments to spend more than they collect as taxes and other sources of revenue every year. Not adjusting for this would thus be like counting one’s overdraft as income, for the debts incurred must eventually be paid[3].

In Spain, another approach to the calculation, the “cost-benefit method”, has sometimes been advanced as a more accurate reflection of reality. In it, the costs incurred by Spanish institutions that are somehow deemed beneficial to everyone, ranging from ministries and shared services to museums regarded as “of national interest” such as El Prado in Madrid, are allocated to all regions regardless of where the expenditure is actually made. However, this method has two major drawbacks. First, the allocation rules may be more or less sensible – why would the costs of El Prado be reallocated but not those of museums located in other Spanish cities? At any rate, they are inevitably arbitrary and therefore introduce a strongly subjective element in a calculation that is meant to be clear-cut and objective. Second, regional spending has a local macroeconomic impact (higher GDP, more jobs, etc.) that cost-benefit allocations disguise: whoever may benefit from their work, it is the people hired by El Prado who work in Madrid and spend most of their income there. It is thus the cash flow method that lends itself best to an objective assessment, as well as elucidating the macroeconomic impact of fiscal balances.

The debate is so lively in Spain, of course, because Catalonia’ fiscal deficit figures are nothing short of shocking by international standards. One rarely, if ever, finds any developed democracy, no matter how progressive its tax and spending policies may be, where any regions are subject to such a high fiscal deficit. In the USA[4] for example, the states acting as the country’s core economic drivers have fiscal deficits amounting to less than half of Catalonia’s, e.g., 4% for New York or 4.2% for California in 2005, and even a state like Connecticut, with a GDP per capita 31% above US average, had a deficit of 7.3% in 2005. In Britain, London’s fiscal deficit, the UK’s highest, was 6.6% of GDP in 2016-2017, while its GDP per capita was 80% above the British average[5]… The comparison makes Catalonia’s case, whose GDP per capita is barely 17% above Spain’s[6] and yet is burdened with a fiscal deficit of nearly 10% of its GDP, all the more outlandish.

The devil in the details

The Catalan case seems even more peculiar when we dive into the details. For instance, from the outside one might expect this huge fiscal deficit to be the unintended result of automatic redistribution rules – e.g. pensions financed by regions with more working-age people and paid to others with an older population. However, the figures tell a very different story[7]. In 2021 for example, Catalonia contributed 19.2% of the Spanish government’s overall revenue, which seems reasonable considering that Catalan GDP is 19% of Spain’s, but only got back 13.6% of the total expenditure… And, if we exclude social security payments and contributions, which in Catalonia’s case are generally balanced, then the contrast becomes a lot starker: 19% of the Spanish government’s tax revenue is sourced from Catalonia, again a reasonable figure, but only 9% is spent back in the region(!). In other words: the more discretionary a spending item, the less likely it is to be spent in Catalonia – or, in Natalia Mas’ words, “whenever the state can choose where to do the spending, Catalonia ends up systematically shortchanged”[8].

This does not happen in Catalonia alone: comparable cases are those of Valencia, on the Mediterranean coast south of Catalonia, and the Balearic Islands. Although for political reasons and unlike Catalonia, their local governments do not calculate their fiscal deficit regularly, data available[9] for 2005 indicate that the Balearic Islands’ deficit, at an outlandish 14.2% of its GDP, was even worse than Catalonia’s, whereas Valencia’s, estimated at 6.4% of its GDP, was in a way even more outrageous, for the region’s GDP per capita was then 8% and is today 12% below the Spanish average, and yet Valencia is still fiscally subsidising the rest of the country. These are the highest fiscal deficits in Spain: even Madrid’s fiscal deficit, despite having Spain’s highest GDP per capita (32% above the Spanish average in 2005), was found to be just 5.5% of its GDP. It may or may not be a coincidence that Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Islands are the three traditional Catalan-speaking regions in Spain – we will dive deeper into this point below.

Nor does it seem to be just a matter of syphoning off income from these three Mediterranean regions to the rest, for Spanish institutions often constrain investment in these regions, particularly Catalonia and Valencia, even when it is largely financed by EU subsidies. This is the case, for example, of the so-called “Mediterranean Corridor”, a high-capacity, high-performance railway line that would run along Iberia’s Mediterranean coast from the Pyrenees to the Peninsula’s southern tip, around a third of which will be paid by the EU. Despite this financial incentive, and despite its covering the route with the greatest demand for transport anywhere south of the Pyrenees, the Spanish government systematically gives short shrift to this infrastructure both by repeatedly delaying its deployment and by designing it with such low-cost features that it will simply be unable to fulfil the objectives it was planned for in the first place… Whilst regions in the central and western Peninsula, where transport demand is five to ten times lower than along the Mediterranean coastline, see a much faster deployment and a much higher-performance design of their equivalent railway corridors[10].

If we are to believe several Spanish politicians responsible for these policies, this discrimination is intentional. For example, in his memoirs, José Maria Aznar (Spain’s Prime Minister from 1996 to 2004) recalls how he specifically decided to accelerate the deployment of transport infrastructure connecting Valencia with Madrid while delaying the one between Valencia and Barcelona, logistically in greater demand. Also under his watch, instead of following the route along the Mediterranean coast – in far greater demand as well as requiring the simpler civil engineering – Spain proposed to the EU that the future European railway corridor should cross the depopulated centre of the Peninsula from Algeciras in the south, via Madrid and Saragossa, to connect with Europe through an incredibly expensive 50 km tunnel under the Pyrenees, thus linking the most depopulated regions in both Spain and France. It is difficult to understand the logic of such an undertaking except for the obvious one – namely, to isolate the Mediterranean coast and redirect traffic and economic flows towards the centre.

Indeed, for 10 long years, Spanish governments run by both major parties – the conservative People’s Party and the socialist PSOE – defended this economically absurd design against the obvious Mediterranean route until the European Transport Commission decided to pull it out of the project eventually approved by the European Parliament in December 2013… Even after that, the Spanish administration reacted by planning a low-cost design for the Mediterranean segments – so low-cost, in fact, that it simply cannot meet its intended objectives – and underfinancing even those works to the point that they are today hopelessly delayed: in November 2022, nine years after the start of the project, 82% of the segments planned for the Mediterranean route were still work in progress.

The social cost of economic discrimination

We could go on listing examples of Spanish government policies that seem deliberately aimed at clipping the wings in economic terms of not only Catalonia but also its neighbours and natural hinterland in Valencia and the Islands – policies that may or may not be reflected in their enormous fiscal deficit. These policies’ welfare impact is huge, and has become particularly concerning since the early 21st century, as the massive wave of immigration these three regions received stretched their public services: between 1997 and 2022 Catalonia’s population went from 6.2 to 8 million, Valencia’s from 4 to 5.3 million and the Balearic Islands’ from 0.8 to 1.2 million[11] – i.e. increments of between 30% and 50% in 25 years. That is not the case of the rest of Spain: in the last 25 years, the Spanish population outside Catalonia, Valencia and the Balearic Island grew by just 12% (from 29 to 32.5 million), and if we also exclude the always-special case of Madrid, which being the capital, has grown at rates similar to those of the Mediterranean coastline, then this rate drops to a paltry 7.5% over a quarter of a century.

Immigrants obviously move to Spain’s Mediterranean regions attracted by economic opportunity and, as they work at their jobs, create value. In return however, they also generate greater demand for public services (health care, transport, education, etc.) which of course under normal conditions could be financed via the government’s share (through taxes, social security payments, etc.) of the additional value these immigrants create with their work. Yet that is not how it has worked: as migration flooded Catalonia as well as Valencia and the Balearic Islands, and as their GDP per capita fell due to the newcomers’ activities being, on average, of comparatively low value added (hospitality and tourism, construction, food processing, etc.), these regions’ fiscal deficit not only did not ease but became an even heavier burden.

The social impact is huge. For example, Catalonia, which has the fourth highest GDP per capita in Spain, drops to the 12th position in terms of its Regional Social Progress Index according to EU estimates[12], whilst the Balearic Islands, with the fifth highest GDP per capita, stand at the 13th position in this ranking. This also helps to explain why so little of Catalonia’s growth has transformed into increased consumption: between 2000 and 2019, Catalan GDP per capita grew by 14.2%, whereas consumption per capita only did so by an insignificant 1.7% – the Spanish equivalent averages being respectively 17.8% and 8.6%[13]. The lack of funds naturally pushed these regions’ autonomous governments to compensate by raising regional taxes – Catalonia and Valencia occupy the two last positions in Spain’s regional tax competitiveness rankings[14] – and if that was not enough, to borrow – which has turned Catalonia and Valencia into the Spanish regions with the highest debt per capita[15].

If mass immigration fuelled by the appeal of tourism and a construction boom was the most obvious feature of this process in the first decade of the 21st century, now that both the Eurozone crisis of the 2010s and the COVID crisis of the early 2020s are over, a second factor has popped up that impacts Catalonia much more intensely than either Valencia or the Islands: gentrification driven by its residential appeal for high income professionals, which raises lease rents and threatens to expel current residents from their homes. These are again growing pains whose impact could potentially be mitigated through policies (e.g., public housing, or improved transport connection between downtown and surrounding areas) financed by the public revenues growth itself generates. Yet the oversized fiscal deficit prevents this, and reduces regionalgovernments either to impotent complaining or, worse, to low-budget populist measures that transfer the cost to the private sector (e.g., general rent freezes, or mandatory “social rate” rents for flats owned by “large landlords”) and, characteristically, only make the problem worse.

Raison d’état

In short, through overly extractive policies and various forms of discrimination, Spanish policies are choking the economic potential of its most promising region, as failure to soften the collateral impact of growth increases social dysfunction, conflict, and general discontent. The question is, why? Here is where we need to understand the specific drivers of Spain’s raison d’état.

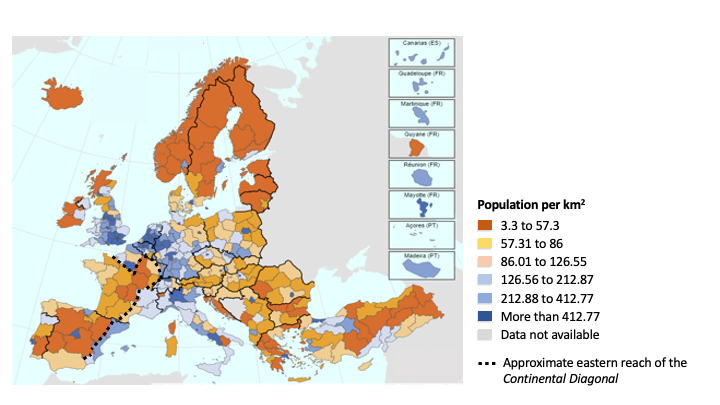

Figure 2: Demographic density in Europe (NUTS2 level), year 2018

Source: Eurostat[16] (the dotted line to indicate the eastern border of the Continental Diagonal has been added for visual clarity)

First, Spain is probably the European state whose demographic map has changed the most as a result of global integration[17]. Look at the highly depopulated area known as the “Continental Diagonal” (Figure 2), which runs approximately from Liège, in Southern Belgium, cutting France in half (where it is known as “la diagonale du vide”, i.e. the Empty Diagonal) and covering most of Spain (where it is known as “la España vacía”, i.e. empty Spain) to end in Portugal just before reaching its more densely populated coastal area. This encompasses old wheat-producing plateaus (“le massif central” in France, “la meseta” in Spain) whose economic and demographic relevance was greatest before the Industrial Revolution but has steadily decayed since. As the most value-adding activities tend to be those that most benefit from economies of scale, and activity also attracts workers who, in turn, demand a whole range of services wherever they live, activity concentration in a few privileged places (which in Western Europe are primarily the axis England to Northern Italy and the one from the Alps to Valencia) not only accelerates with economic integration but also ends up taking a momentum of its own.

In most of Europe, however, this shift tends to reinforce the old centres of power, as global economic integration tends to increase their economic weight: think of the Seine and Rhone valleys in France (Paris, Lyon, Marseille) or the Atlantic coast in Portugal (Porto, Lisbon). The same pattern repeats across Western Europe: economic integration favours London and England’s South-East, Western Germany, the centre-north of Italy… Spain, conversely, sees its population and its economic activity consistently moving away from its historical power centre in Castille and primarily towards, the Mediterranean coast – the only exception being Madrid, the third–largest metropolitan region in the EU, proudly defying market forces from the middle of the most depopulated European region south of Lapland.

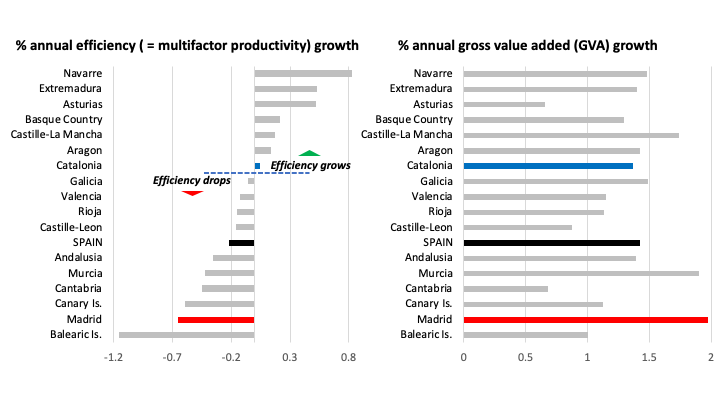

Figure 3: Efficiency and value-added growth in Spanish regions, 2000-2015

Source: Data from Ivie (2019)[18]. Diagram and analysis from Gracia (2021)[19]

This explains why Madrid’s economic success presents some strange features. For example, to the right of Figure 3, which shows gross value-added growth (i.e., for all practical purposes, GDP growth) between 2000 and 2015, Madrid clearly appears as the fastest-growing region in Spain. Yet, to the left, the evolution of productive efficiency[20] (i.e. the economy’s ability to produce more output per unit of input) over the same period tells quite a different story. That the most touristic regions (the Balearic and Canary Islands) would have lost efficiency is no surprise: nothing is more inefficient than an empty building, and these regions, after a spectacular construction boom, found themselves with a lot of empty property. That the emptiest regions in empty Spain (e.g. Asturias or Extremadura) would increase their efficiency is no surprise either: as economic activities drift towards more attractive places, those that remain are obviously the most efficient of the lot, so their average improves. The real question mark is Madrid.

Indeed, why would Madrid’s efficiency drop more than that of any other region except the Balearic Islands when the economies of scale of its high value-added activities should have the opposite effect? Because many more productive resources (both labour and capital) have been poured into it than efficiency would justify – and since most of this labour and capital belong to the private sector, this must be because the margins of those activities in Madrid are so much greater than elsewhere to justify such waste. And why would those margins be so much greater than elsewhere in an otherwise competitive market? Because of the presence in Madrid of Spain top public decision-making institutions, which reward companies whose behaviour is aligned to their political intent and, since Spain’s institutional quality is among the lowest in Western Europe, also to the personal interests of some decision-makers.

Thus, for example, despite Madrid hosting the bulk of the Spanish financial sector, its financial market is tiny compared not just to those of London and Paris but also Frankfurt, Zurich, Amsterdam and Geneva. Spanish governments can leverage their economic and regulatory power to nudge Spanish banks’ headquarters and shared services to the capital, but European financial markets are fiercely competitive, and Madrid can hardly play in that league.

That is also why, to pose another example, Madrid’s Research & Development ecosystem consistently trails behind Catalonia’s – despite Madrid’s R&D budgets being consistently greater – in terms of results reflected by international patents registered per million GDP for example, or in the share of published articles among the world’s 10% most quoted[21]. The reason is that Catalonia, and particularly its capital, Barcelona, has both a more attractive (even touristic) environment for young knowledge professionals and a substantially R&D-relevant private local industrial base (e.g., in pharma). In an integrated, competitive EU market where the Spanish government’s R&D financing competes with EU public funds and with multinationals, the advantages that Catalonia offers may trump, at least in some areas, Madrid’s long-time advantage as Spain’s seat of power.

There are many more examples of activities where Madrid’s competitiveness does not measure up either to its foreign competitors’ or to that of its eternal rival: Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia. Yet, while the comparison with foreign competitors is easy to accept as a fact of life (there will always be someone in the world that is better at this or that), the latter triggers an old atavistic conflict, for in Spain, the Catalans constitute a traditionally unpopular minority.

The Spanish disease

This brings us to the heart of the problem. Relying on his deep, global academic perspective on social and political conflict, and not just his own Catalan experience, Carles Boix, Professor of Politics and Public Affairs at Princeton University, summarises it as follows:

In my view, Spain is sick. Its sickness, which takes the shape of a compulsive obsession, is called Catalonia. And the internal discomfort is so deep that, against the prediction everyone made during the democratic transition, neither the economic growth nor the political liberties or the social transfers of the last decades have been able to soothe it.[22]

The Catalan case is akin to those of other groups that have traditionally taken entrepreneurial roles in the economies of otherwise traditional societies: Jews, Greeks, Armenians, Arab Christians, East-African Indians, South-East-Asian Chinese and other so-called “middleman minorities”[23]. Just like them, Catalans have historically spearheaded industrialisation and economic development in Spain and, just like them, have become the target of their neighbours’ envy and hate. Resorting to anti-Catalan feeling to advance a political career is such an old, well-known ploy in Spain that it even has a byword deriving from the name of a politician who made it his trademark: Lerrouxism. The ploy is so frequently used that, when politicians and celebrities spout hate speech against Catalans, they barely cause a stir in the Spanish news, whereas politically incorrect statements against any other minority invariably cause widespread outrage.

There is actually an old Spanish reformist tradition that poses “Spain’s catalanisation” as the way to modernise the country, but even this strand of literature implicitly regards Catalans as an alien people. Already in the 1770s, Enlightenment authors like Francisco Nifo and José Cadalso proposed that all Spanish provinces imitate Catalonia because it was “a little England” (Nifo)[24] and its inhabitants “the Dutch of Spain” (Cadalso)[25]. Two centuries later, in 1978 and just a few months before the (so far) last Spanish Constitution was approved, conservative journalist José María Carrascal proposed again to “catalanise Spain”[26], because in his view, the Catalans displayed the “civic virtues” that characterise age-old democratic peoples like “the Swiss and the English”. Ten years ago (September 2013), a conservative politician, Esperanza Aguirre, put forward the same idea in a speech she gave in Barcelona[27]. Flattering as these proposals might seem to Catalans, the experience of similar conflicts should remind us that praise flips into hatred just as easily as admiration turns into envy: just compare Friedrich Nietzsche’s praise of the Jews in Beyond Good and Evil[28] with the words (and deeds) of the Nazis who claimed to be his admirers.

Two new factors may have made the conflict even worse over the last few decades: the rise of the welfare state and European economic integration. Catalonia’s fiscal deficit has existed at least since the late 19th century, but until the 1980s, Spanish government spending was no more than 20% of Spain’s GDP, so the burden was more tolerable. Since the 1980s however, Spain has become a full-blown welfare state whose expenditure represents close to half of its GDP. So, as the overall tax burden has become much heavier, so has the fiscal deficit. In parallel, as part of the price for European economic integration, Spain has given up many economic control tools such as tariffs, monetary policy and various forms of discretionary subsidies. European integration has brought widespread prosperity but has also accelerated Spain’s economic drift towards the Mediterranean coast. As economic activity is also a form of power, left to market forces, Spain’s internal power balance might thus eventually tip in the same direction – which may well have triggered the Spanish establishment’s self-protecting instinct. Yet at the same time, as the regions most favoured by the market happen to be those with the strongest Catalan cultural substrate, starting with the largest of the lot, namely Catalonia itself, it becomes just too tempting to leverage that old popular hatred against a people that has always seemed readier to ply the winds of modernity.

An oversized fiscal deficit and other discriminatory economic measures may therefore reflect the use of the state’s coercive power to redirect economic flows towards regions, businesses, and purses more to its élite’s liking – even at a colossal cost in terms of loss of economic efficiency and thus ultimately welfare. Such discriminatory measures might not be easy to justify to the public in a democratic system, but in Spain they would be facilitated by those old prejudices against Catalans – which, unlike other forms of cultural prejudice (e.g., against immigrants’ cultures, or against LGTBI communities), are today not just tolerated but also echoed, and even actively promoted by some Spanish mainstream media anchors (notably in the COPE network).

This is where Spain’s institutional promotion of Madrid’s economic role plays in. To attract high-value-added activities towards a location that reinforces Spain’s historical power balance, these activities must be offered a home in a major metropolitan area with the scale, services and opportunities that they require, and within Spain, only Madrid and Barcelona can compete in this league. With market forces favouring Barcelona as a naturally more attractive location (more touristic, industrially relevant, logistically accessible…) and state institutions using their coercive power to redirect wealth flows towards Madrid (Spain’s traditional seat of power), the bitter conflict between the two metropolises can only get worse. Ramon Tremosa – an author, professor of economics at the University of Barcelona, and a Member of the Catalan and European Parliaments, as well as the former minister of Business and Knowledge of the Catalan Government (Generalitat) – puts is succinctly: it is a struggle of “the state against the market”[29].

For the last 20 years, the conflict has followed a steady pattern of escalation. To the Spanish governments’ economic discrimination, at a time when, as we have seen, new economic opportunities arrived together with a whole host of social spending needs, the Catalan political and social forces reacted first by promoting a new Statute of Autonomy in Spain’s parliament, including some explicit rules for fair resource allocation across regions. Against that however, Lerrouxism raised its ugly head and many Spanish politicians stepped up their hate speech against the Catalans: a good portion of the press lambasted the proposal, more than four million signatures against the Statute of Autonomy were collected around Spain, and despite its approval after substantial watering-down by the Spanish parliament, a heavily politicised Constitutional Court all but overturned it.

The signature collection episode was perhaps the most revealing: since Catalonia has a bit over five million people with a right to vote, four million signatures “against the Catalans” (for this is how this was often peddled) imply that any Spanish politician has more to lose than to gain from offering any fair deal to Catalonia, since Catalan voters could never outweigh the votes of those who are willing to punish the politician for offering any advantage to a people they dislike.

This refusal to entertain relatively low-key solutions to a pressing problem pushed the Catalan side into options that would not require Spanish institutional support to be implemented – and this obviously led very quickly to a push for independence. The Spanish government’s response was violence and repression, while expressions of hatred against Catalans were heard in the media and on the streets. Perhaps most significantly, since the failed 2017 attempt to make Catalonia independent, next-step proposals by Spanish institutions and media have swung between heavy-handed repression and pardons to foster reconciliation, yet very seldom, if at all, have they included any credible approach to address the core problem. This may mean that the weight-power balance preservation and popular prejudice for those posing these proposals is so high as to trump the obvious aim of making any solution sustainable in the long run.

This is the ugly moon so many fingers are pointing at. As long as no solution to the core problem is put forward, the issue may temporarily remain subdued due to fear of political repression and low expectations for change, but over time is bound to grow and fester. So, stay tuned: this saga is far from over.

Eduard Gracia is an economist and MBA, as well as author of several books and articles about economic topics. For nearly three decades he worked as a management consultant based first in New York, then London and finally Dubai. He is currently a lecturer of international economics at the University of Barcelona.

Notes

[1] La balança fiscal de Catalunya amb l’Administració central. Departament d’Economia i Hisenda (gencat.cat)

[2] “Un ofegament financer sostingut, injust i deliberat” Dèficit fiscal històric: 22.000 milions | L.B | barcelona | Economia | El Punt Avui

[3] Bizarrely, even this obvious point has been questioned by otherwise intelligent Spanish unionist characters like Josep Borrell, today’s EU Foreign Relations Commissioner (as economist Xavier Sala-i-Martin pointed out a few years ago Encontrados los millones de Borrell! | @XSalaimartin Blog)

[4] Manifest Economistes pel Benestar Economistes pel benestar – Manifest (google.com), 2005 data.

[5] London’s fiscal surplus drifts further away from rest of UK — ONS. London fiscal deficit (in UK terminology this is counter-intuitively referred to as “surplus”) was

[6] Year 2021 INEbase / Economía /Cuentas económicas /Contabilidad regional de España / Últimos datos

[7] El dèficit fiscal de l’estat espanyol amb Catalunya ja voreja els 22.000 milions (vilaweb.cat)

[8] “Allà on l’estat pot escollir on fa la despesa, Catalunya en surt malparada sistemàticament” Els 22.000 milions de raons per a dir prou! (vilaweb.cat)

[9] Reyner, Josep (2020): Informe Euromedi. Anàlisi de les potencialitats de la regió mediterrània i de les limitacions que li son imposades. Fundació Vincle Informe-Euromedi-170×220-ENG-2022-web.pdf (fundaciovincle.com)

[10] For a detailed study see Gracia, Eduard (2022): Bastons a les rodes. El Corredor Mediterrani i la lògica del poder a Espanya. Fundació Vincle fundaciovincle.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Bastons-a-les-rodes-al-Corredor-Mediterrani-Eduard-Gracia-Fundacio-Vincle.pdf

[11] INE Población por comunidades y ciudades autónomas y tamaño de los municipios.(2915) (ine.es)

[12] European Regional Social Progress Index 2020 Inforegio – European Social Progress Index (europa.eu)

[13] Cambra de Comerç de Barcelona (2020): Convergència amb els “frugals i dèficit fiscal (p. 8) Microsoft Word – 2020 09 CAT vs Frugals – DEF_ok.docx (cambrabcn.org)

[14] Índice Autonómico de Competitividad Fiscal 2022 IACF-2022-WEB.pdf (fundalib.org)

[15] Fundación BBVA (2023) Endeudamiento de las comunidades autónomas Endeudamiento_CCAA-1.pdf

[16] Statistics | Eurostat (europa.eu)

[17] For a more in-depth analysis see Gracia, Eduard (2021): Integració europea o marginació espanyola. El futur bifurcar de Catalunya, el País Valencià i les Balears. Fundació Vincle Integracio-europea-o-marginacio-espanyola-Eduard-Gracia-Fundacio-Vincle.pdf (fundaciovincle.com)

[18] Ivie (2019): La productividad de la economía valenciana en el contexto regional: determinantes. IvieLAB i Generalitat Valenciana IvieLAB. La productividad de la Comunitat Valenciana en el contexto regional: determinantes – Web IvieWeb Ivie

[19] Gracia, Eduard (2021): Integració europea o marginació espanyola. El futur bifurcar de Catalunya, el País Valencià i les Balears. Fundació Vincle Integracio-europea-o-marginacio-espanyola-Eduard-Gracia-Fundacio-Vincle.pdf (fundaciovincle.com)

[20] Measured as what economists call, somewhat cryptically, Multifactor Productivity

[21] According to the European Regional Innovation Index EIS 2023 – RIS 2023 | Research and Innovation (europa.eu)

[22] “Al meu entendre, Espanya està malalta. La seva malaltia, que té forma d’obsessió compulsiva, es diu Catalunya. I el desfici intern és tan profund que, contra el pronòstic que tothom feia durant la transició, ni el creixement econòmic ni les llibertats polítiques ni les transferències socials de les darreres dècades l’han pogut apaivagar.” (p. 114). Carles Boix (2012): Cartes ianquis. Un passeig sense servituds per Catalunya i el món. Acontravent. Amazon.com: Cartes ianquis. Un passeig sense servituds per Catalunya i el món: 9788493972288: Carles Boix: Libros

[23] Middleman minority – Wikipedia

[24] 1770 Francisco Mariano Nipho: opinió de Catalunya – Museu d’Història de Catalunya (mhcat.cat)

[25] cartas-marruecas.pdf, Carta XXVI

[26] ABC_19780203011 (lidiapujol.com)

[27] 610,8 KM = 0 KM – Esperanza Aguirre: “Hay que catalanizar España” – Blogs Expansión.com (expansion.com)

[28] beyond-good-and-evil.pdf, Aphorism 251

[29] “L’Estat contra el mercat” Tremosa, Ramon (2020): Catalunya, potencia logística natural. L’Estat contra el mercat. Pòrtic Catalunya, potència logística natural: L’Estat contra el mercat: 148 (P.VISIONS) : Tremosa, Ramon: Amazon.es: Libros

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the CGI or its contributors. The designations employed in this publication and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CGI concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers.