Libya, the Government of National Unity, an opportunity for peace after ten years of war?

30/04/2021

(Input from Sarah Feuer, Ben Fishman, Wolfgang Pusztai, and Aude Thomas is taken from e-mail interviews that these four experts have given to the author in exclusive for this Catalonia Global Institute article.)

Libya, marred by a decade of armed conflict and division, has sworn in an interim unity government led by businessman Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh. He is expected to replace two rival cabinets that have dominated the North African country’s west and east respectively, each with different foreign backers, since 2014. The new Government of National Unity (GNU) stems from talks initiated in November 2020 at the UN-sponsored Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF) and will be responsible for restarting reconstruction efforts — including economy, infrastructures, and administration — and preparing the way towards the December 24th general election. Still, substantial challenges remain, and many of them have to do with the geopolitical implications of the process. Over the years the conflict has increasingly become a proxy war between rival regional powers.

A 10-year, multi-faceted conflict

Within the context of the so-called “Arab Spring”, the regime of Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi, who had ruled unchallenged since 1969, was toppled by an armed rebellion in 2011, leading to the First Libyan Civil War. However, this did not bring about the substitution of one stable regime by another, but instead opened the way to factional violence (2011-2014), and subsequently to a Second Libyan Civil War (2014-2020). To summarise, the whole process resulted in the country’s division between the western region of Tripolitania, ruled by the Government of National Accord (GNA), and the eastern region of Cyrenaica, under the control of a Tobruk-based government – more formally, the Second Abdullah Al-Thani Cabinet.

The Tripoli-based GNA was initially meant to be the unified government of Libya under the auspices of a United Nations-led effort in 2015 (the so-called Libyan Political Agreement). It thus received official recognition from the UN itself, and from the EU. Domestically backed by an array of local militias and some remnants of the Libyan Army, it enjoyed foreign support from Turkey, Qatar, and — at certain times — Italy. Meanwhile, the Tobruk government in the east did not join the GNA, it continued to exert control over the eastern regions — including the armed forces loyal to it, the Libyan National Army (LNA) led by former general Halifa Khaftar — and was supported by Egypt, the UAE, France, Saudi Arabia, and Russia.

In Libya’s mostly barren southern two-thirds — the southwestern Fezzan region and the southern lands of Cyrenaica — several local armed groups emerged with their own agendas. They play a critical role for whoever wishes to control the area, including its oil industry and its smuggling and trafficking routes crossing into neighboring countries. Some of these groups are Tuareg or Tebu, who have links to their cross-border ethnic kin in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Chad, and independently negotiate their alliances with either of the aforementioned blocs, also shifting them if in their interest.

The infighting came against the background of a volatile situation on the ground in which hundreds, if not thousands, of militias operate, mirroring Libya’s diverse geography and social fabric. Libya is arguably the North African country with the weakest sense of nationhood and state-building process over the last decades. Demands for autonomy have been voiced by Tuareg and Tebu leaders, as well as by an Amazigh local council in the Nafusa mountains; in Cyrenaica, calls for federalism or even secession can be heard from time to time.

All fed up with the decade-long division and infighting

Against that background, American diplomat Stephanie Williams, the Acting Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations for Libya, launched the LPDF as a series of Libyan domestic talks in which representatives from all regions ultimately agreed on a mechanism to select a unified executive authority for the war-ravaged country. Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh (Tripolitania) was elected as the new prime minister, while Mohamed al-Menfi (Cyrenaica), Musa al-Koni (Fezzan) and Abdullah Hussein Al-Lafi (Tripolitania) were selected as Chair and Vice-Chairs of the Presidential Council.

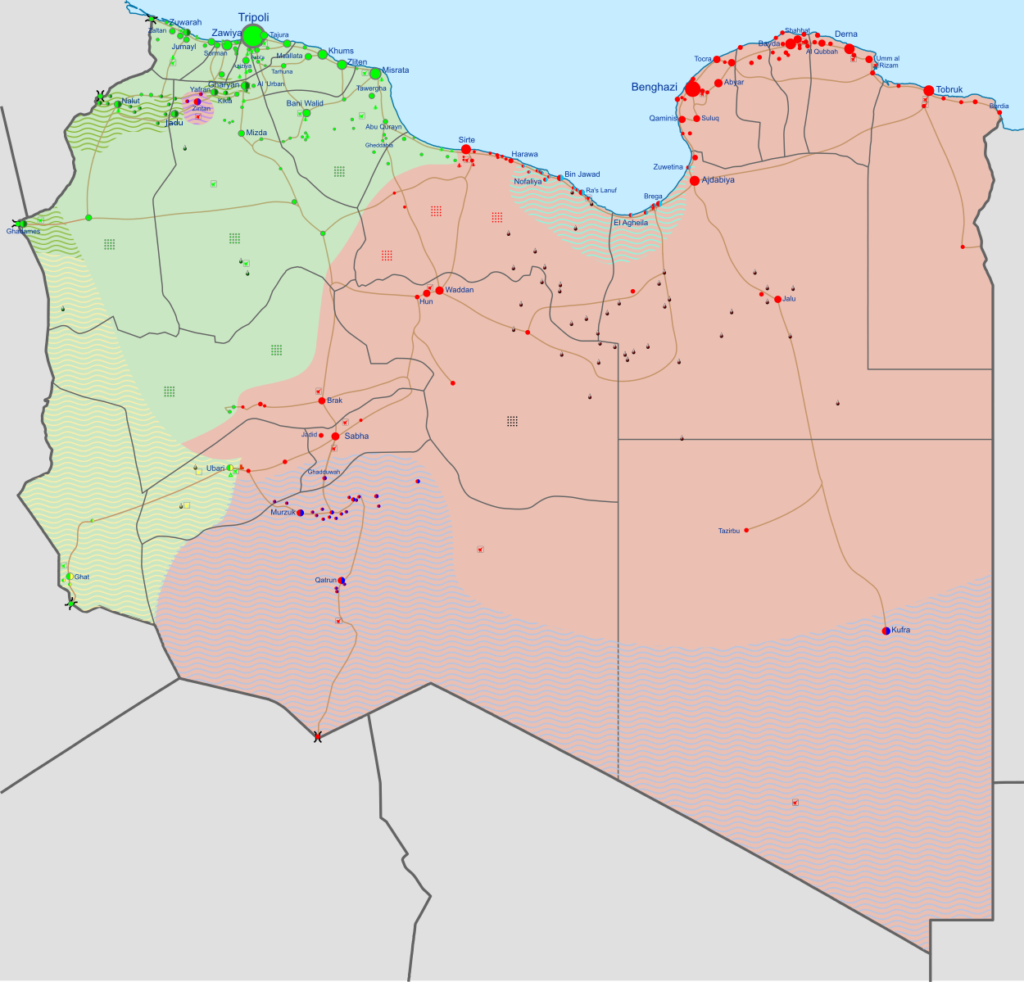

Llegenda: verd Govern d’Acord Nacional; vermell Govern de Tobruk; blau mílicies locals. Crèdits: Wikipedia

How can we explain that the UN-sponsored Libyan initiative has yielded positive results in such a relatively short period of time? According to Wolfgang Pusztai, senior advisor at the Austrian Institute for European and Security Policy (AIES), the military stalemate between the LNA and the GNA forces, the “broad desire of the Libyan population for an end of fighting and a political change” and the “persistence” of Stephanie Williams with the LPDF approach, “regardless of several setbacks,” are to be credited. Moreover, “the willingness by many Libyans and by the international community to accept several shortcomings of the incoming government [the GNU] in order to replace two corrupt governments,” namely the GNA and the Tobruk-based government, “by one government, even if this starts off with a vote-buying affair,” has also helped.

Of course, the new interim government has an enormous task before it. “The GNU’s main challenge at the domestic level will be to provide security and prevent renewed clashes between local armed groups in Tripolitania, which have a tendency to use violence in the absence of a common enemy – namely Khalifa Haftar,” argues Aude Thomas, research fellow at the Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique (FRS), as “armed groups will most certainly fight to keep their privilege and position within strategic institutions.” Along with the need to “cope with the Covid-19 pandemic” in a country where “medical infrastructures have suffered a lack of investment and numerous shelling during armed combat,” Thomas underlines that “the GNU will also have to avoid being the instrument of local rivalry – a difficult task knowing the cabinet was constituted in order to reach a balance of power between Libya’s three regions to prevent any political deadlock.”

In the longer run, “future arrangements reflecting the makeup of Libya and its political representation need to be decided through a transparent national process, whether it is through a renewed National Dialogue that was aborted when Haftar attacked Tripoli in April 2019, through the recent LPDF, which the UN convened specifically to be geographically inclusive, a constitutional referendum, or some other format,” says Ben Fishman, a senior fellow at The Washington Institute. “What seems clear from the vast majority of Libyans, even the so-called federalists who seek relative autonomy in the East, is that they want to keep Libya as a unified country. It will take some time to work out the specific political and economic arrangements for regions, sub-regions, and minority groups.”

An opportunity for Turkey’s Blue Homeland doctrine?

Yet another essential factor for Libya’s division is the fact that, over the last ten years, several powers have tried to fill the vacuum and seize the opportunities created in Libya. Some of them are seeking to rejuvenate and assert their centuries-old influence over the country — such as Italy, Turkey, or Egypt — to which an array of other countries, such as France, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the United Arab Emirates, must be added.

At this point, it would appear that Turkey might be getting the upper hand in Libya. On the one hand, the man elected as the new prime minister of Libya, Abdul Hamid Dbeibeh, as well as other members of his family have business ties to Turkey and hails from Misrata, a city known for its longstanding links with Turkey dating back to Ottoman times. On the other hand, Turkey’s successful military intervention in the Libyan war during 2020 was critical to allow GNA forces to put an end to Khalifa Haftar’s offensive in Tripolitania. Turkish drones — which were crucial also for Azerbaijan’s victory over Armenian forces in the 2020 Karabakh war — have been credited as a game-changer in the conflict leading to the GNA’s victory over Haftar in Tripolitania. In this, Turkey has managed to stop military penetration by Russia — which allegedly sent in mercenaries via the Wagner Group, a private contractor closely linked to the Russian state — into Libya’s west, and the UAE, which in their turn had supplied Haftar’s forces with drones.

“Turkey has a deep strategic interest in a long-term relationship with Libya,” says Ben Fishman, “not just for security commitments, but for economic and commercial opportunities. They are looking to restore billions of dollars in pre-revolution contracts, which they maintained both in the west and east of the country.”

However, it is still far from clear whether Dbeibeh’s election heralds a period of Turkish hegemony in Libya. It must be recalled that the GNU is but an interim government that is expected to be replaced by another after the December 2021 election. Lacking a strong power base, Dbeibeh and Mohamed al-Menfi “have raised no serious concerns among any of the rival parties,” as both “are seen as blank pages that each party hopes to fill in line with its interests,” writes Turkish foreign policy analyst Fehim Tastekin in this Al-Monitor column. According to Turkish state-run Anadolu Agency, Dbeibeh has also re-committed to the November 2019 maritime deal that the GNA signed with Turkey. The agreement was very controversial and was reported as being a violation of the Law of the Sea Convention by all of Turkey’s Mediterranean neighbours. The deal builds on Turkey’s Mavi Vatan, or Blue Homeland, concept. “According to this doctrine, islands do not have an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), but only 6 nautical miles of territorial waters. Consequently, all the Greek Islands, and even Cyprus, would not have an EEZ,” explains Wolfgang Pusztai.

Zona Econòmica Exclusiva acordada entre Líbia i Turquia en el marc de la doctrina “Pàtria Blava”. Crèdit Wikipedia

Such an approach means that, in Turkey’s eyes, its potential EEZ spans well into the middle of the Eastern Mediterranean Sea and shares a maritime border with Libya’s EEZ, to the detriment of Greece and Egypt. Unsurprisingly, these two countries, as well as Cyprus, deem the Blue Homeland doctrine as aggressive, amid Turkey’s increasing aspirations to become a regional power. “The Mavi Vatan doctrine is a key element in President Erdogan’s strategy for Turkey’s economic recovery – gas exploration- and the expansion of influence in the Eastern Mediterranean as well as in the Black Sea,” says Pusztai, who argues this is why the 2019 deal “is an important strategic end for Turkey and a centrepiece in its Libya policy. As the coast facing Turkey in Libya is in eastern Libya, in Cyrenaica, it is crucial for Turkey that Libya remains a unified state ruled by a friendly government.”

Foreign presence (and military division) set to last on the ground

One month before the LPDF was launched, delegates on behalf of the GNA’s Libyan Army and of Tobruk’s Libyan National Army reached a ceasefire deal in Geneva under UN auspices. The deal set a three-month deadline for the withdrawal of mercenaries and foreign fighters. But Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan recently signalled he was unwilling to do so until all other foreign actors — namely Russia, the UAE, and Egypt — do the same, and even told France — also Ankara’s rival in Libya — to withdraw its forces from several Sahel countries.

“France’s main interest in Libya is security for the EU’s southern flank and for operations conducted by the French army in the Sahel region,” points out Aude Thomas, who says the new government “gives a chance to France to regain influence” in Libya, “damaged by Paris’s support to Khalifa Haftar during the 2019 campaign against Tripoli.”

“Southern Libya, especially the southwestern province Fezzan, has a key function for the stability of the wider southern Sahara region,” coincides Pusztai. “Currently Fezzan serves more or less as a safe haven for groups like AQIM or the Islamic State, who are active in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. This is also the main driving element for the French involvement in Libya, as terrorists from Fezzan are harming vital French interests in neighboring countries (e.g. the uranium mines in Niger). Consequently, as Haftar’s Libyan National Army has at least loose control over wide areas of the south, the French have counterterrorism cooperation with him,” the AIES advisor says. The reopening of the French embassy in Libya, seven years after being closed, signals the renewed importance that Paris gives the country, and especially the new opportunities that can open up with the GNU.

As regards Italy, and in addition to historic reasons dating back to colonial times, “by virtue of geographic proximity, energy, security, and migrant concerns, [it] will continue to play an important role in Libya,” says Fishman. The central Mediterranean route, which connects the Libyan and Tunisian coasts to Italy, “has been one of the most active and dangerous routes for people crossing to Europe by sea,” with a record 181,000 maritime arrivals in Italy in 2016, ACAPS reports. Control over this route is deemed strategic by Rome. Besides, Italian companies — oil and gas company Eni at the fore — have huge economic interests both in Libya’s western and eastern regions. This and the fact that Italy’s “diplomats are some of the most familiar with Libya’s complex dynamics,” as Fishman puts it, help explain Italy’s somewhat ambiguous stance during the conflict, mostly supporting the GNA while at the same time cultivating relations with Haftar. Rome also has reasons to partner on the one hand with Ankara while on the other with Paris, which adds to Italy’s ambiguous position. But also taking advantage of this, “Italy can play a leading role in pressing for unified EU support to Libya in this sensitive stage of the transition,” Fishman considers.

It has emerged that Ankara might accept sending home Turkish-backed Syrian mercenaries deployed in Libya. “To have a long-term and responsible relationship with the new Libya government, [the Turks] have to fully support the UN peace process and start by withdrawing Turkish-backed mercenaries,” argues Fishman. “Most probably [it would be] a gesture of goodwill to ease tension with the EU and Biden’s administration to prevent additional sanctions”, says Thomas, but the FRS fellow believes the Turks would still keep their own forces on the ground “to strengthen their military footprint” in Al-Watiyah, Misrata and Khoms. “The same logic applies to Wagner. They have consolidated their presence in eastern and southern Libya where oil fields and strategic military bases are located. As for the UAE, I don’t believe they will leave Libya to the Turks. They have reportedly established strong ties with Sudanese armed groups and discussed recently their longstanding presence in Libya.”

In this context, Thomas believes that “for now, we will observe a continued military division” of Libya, as “the GNU objective — as stated by Prime Minister Dbeibeh — is to avoid renewed clashes between the east and west during this transitional period.” On the other hand, even if Haftar has not been awarded a post in the GNU, he is widely expected to seek control of the future Ministry of Defence. “The subject,” the FRS researcher argues, “is too sensitive and complicated to be solved in upcoming months.”

Thus, a rapid withdrawal of all or most foreign military actors should not be counted on. “I believe the foreign presence is expected to last. It might be eased in the upcoming weeks or months, but won’t vanish for sure,” concludes Thomas, as regional powers “have invested a lot and thus will not leave without compensation (contracts, military bases…)”. Libya represents a significant market for reconstruction projects. Those forces “also represent a guarantee for local actors should the political process fail,” the FRS researcher argues.

And indeed, to what extent is this political process in danger of failing? Or rather, does the GNU have better prospects to survive and unify the country than the GNA had in 2015? “My sense of developments in Libya these days is that the newly established GNU may manage to succeed where previous governing structures failed, but only if it garners a more widespread legitimacy within Libya (in both the east and west), something its predecessor, the GNA, sorely lacked. It will also be necessary to reduce the influence of foreign actors such as Turkey, the UAE, and especially Russia,” research fellow at Israel’s Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) Sarah Feuer argues. “[But] I don’t see much indication from Russia and other outside actors that they intend to reduce their presence. A key dynamic to watch will be Russian-Turkish coordination.” Interestingly, the same can be said of other regional scenarios, such as Syria or the Caucasus.

A couple of issues to reflect on in Catalonia

As seen, the Libyan case shows how actors sharing a place in first-order international alliances (EU and NATO) can lend support to different or opposing sides in conflicts, even — or because of that — if they are close to their borders. This is the case for Italy and France, who appear to have subordinated their role in those alliances to their own national interests, following clearly different strategies — even if, to do that, they needed to support a non-UN recognised actor, such as France with Haftar.

Furthermore, Libya has become yet another scenario in which the powers on which Catalonia’s international action has traditionally set its eyes — the EU and the United States — are of relative importance vis-a-vis other (re)emerging actors such as Turkey, Russia, or the UAE. As is happening in Nagorno-Karabakh and Syria, this string of actors, can be in such a strong position that it allows them to determine the course of the conflict, in the face of a diminished influence — whatever the reasons — of the western powers.

David Forniès is a journalist specializing in international politics with a focus on diversity.