Elections in Brazil, the origins of polarization

04/10/2022

On Sunday, Brazil held its 16th election since its democratization in 1988. International media has focused on the possibility that these elections will become the first to be contested, in a manner reminiscent of the presidential elections in the United States two years ago. This has become a possibility after a period of intense polarization, which most media portrays as having started with the presidency of the incumbent candidate, Jair Bolsonaro. The current polarization, however, has deeper roots.

Reducing the political divides to two confronted positions is not a new phenomenon in Brazil. After the dissolution of the military regime, two groups emerged in the country along the socialist-liberal dimension. On the one side, the left-wing Marxist social movement united under the Workers Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, with Lula as its charismatic leader), and on the other side, the Social Democratic Party of Brazil (PSDB) with the young social scientist Fernando Henrique Cardoso as its leader.

From the Marxist left, the accusations against the liberals were about a supposed blind alignment with the Global North and the privatization of strategic state-owned companies. The liberals accused the left of lack of responsibility and attempted to force divisions between rich and poor, black and white, or men and woman. As the Brazilian civil society was experimenting with the new possibilities of life under a democracy, there was plenty of space for conservatives and liberals to grow their reach and organize themselves while avoiding conflict.

After the first election of Luis Inácio Lula da Silva in September 2002 , the left started to pursue its moral agenda, calling the social movements and intellectuals to design how the values of the left would fit the government structure. This extended the polarization of economic policy to moral issues, religion, and culture in general. We can call that the USAlization of Brazilian politics. But yet, there is another power worth mentioning in this transition to generalized polarization: the corporate media. From the moment Francisco Assis de Chateaubriand launched the first TV show to the point Globo Network became the second largest TV network in the world, corporate media consolidated as a true state power in Brazil. Governments have changed, but the families that own TV networks in the country stay the same. This is worth mentioning because the media played a very important role in linking corruption with the Workers Party and giving Bolsonaro his fame.

Despite the increasing polarization, Lula ended his government with the highest approval rate in history. At the end of his second term, it stood at 87%. This figure was new to the Brazilian reality, particularly after two terms filled with corruption scandals. From the very start of Lula’s first government to the last day of Dilma’s cabinet, the accusations of corruption coming from large media corporations were continuous.

Protest everything

Then, in 2013, in Sao Paulo, a group of students (organized under the name Movimento Passe Livre) started to protest against the rise in the price of bus tickets. The slogan was “It’s not for the 0,20 cents, but for what it means”. The police violently repressed the protesters, which inflamed the demonstrations, which spread from São Paulo to several big cities in Brazil. Then it was about corruption. Then against corporate media. Then against the establishment. Then it was about literally “everything that is out there” in a sentence coined by the protesters.

Suddenly there were protests against everything every day for months in several cities of Brazil. The agenda of the protests merged national and local issues.

In 2014 most protests were against the World Cup in Rio de Janeiro and the idea of spending money on new Stadiums in a country with more fundamental challenges. The turning point was that within these eclectic sets of issues, small right-wing groups started incorporating their own demands, such as military Intervention in Brazilian politics.

The Brazilian political spectrum: From 32 political parties to 2 sides

In 2015, the most powerful man in the country was the President of Congress, Eduardo Cunha, and the most powerful party was the Party of the Democratic Movement of Brazil (PMDB). At one point, even The Economist compared him with Frank Underwood, the character from House of Cards, a popular TV show. For the first time, a politician from the “Centrão” held keys to all major decisions, and his conservative moral agenda started to cause discomfort in the leftist social movements.

His framing as a centrist politician, however, did not contribute to de-escalating the deepening of the political divide. This was most evident when he accepted accusations against Dilma Rousseff, the successor of Lula, of fiscal irresponsibility. This meant the start of an impeachment process, effectively reducing the 32 political parties with parliamentary representation to only two sides. One denounced a Coup d’état against Dilma, and the other accused her of political crimes.

To win the narrative war of the impeachment, the conservatives aligned with liberals, and even with extreme right-wing social movements. On the other side, progressives aligned with old critics of the Workers Party and with revolutionary movements. Dilma was defeated, and her government paved the place for the government of her ex-Vice President, Michel Temer, who had coordinated with Eduardo Cunha to impeach her.

While the Workers Party struggled to reconstruct itself outside the presidency, Michel Temer started to build its government with ex-allies and a more conservative approach. During Temer’s term, another piece of the lego of Brazilian politics in recent history unfolded the Car-Wash Operation. The core team of the operation were the state attorneys and the Federal Judge Sérgio Moro, and what started as another criminal investigation suddenly changed the course of Brazilian politics when ex-President Luís Inácio Lula da Silva was arrested. By 2018 Lula was the first in all polls, and the left interpreted his prison sentence as politically motivated. With Lula out of the race, Bolsonaro won the election with a campaign against corruption and a strong focus on reviving traditional values.

With a very conservative congress, support from the financial market, industry leaders, and the ex-Federal Judge Sério Moro as its Minister of Justice, Bolsonaro embodied right-wing hopes of restoring the conservative moral compass.

The (lost) fight for a third option: Moro and Ciro

In the months leading up to the elections, there have been two attempts to build an alternative to the polarization between Lula and Bolsonaro, led by former allies of both presidents. Ciro Gomes (Democratic Labourite Party), the ex-minister, Governor, and Mayor, was once a strong ally of the Workers Party but turned critic of Lula’s attempt to keep the centrality of the Worker’s Party to the left-wing spectrum. The tone of Ciro’s criticism against Lula increased, and so did the reaction of the Worker’s Party, the main theme of the criticism is about highlighting the similarities between Lula and Bolsonaro.

Although Ciro’s campaign still has its niche of supporters, the lack of resources, his intellectual tone, and the success of the Worker’s Party against him reduced his chances of winning to a minimum, and as the polls closed, Ciro had only 3% of the votes. The other “third path” candidature by Sergio Moro was a stillbirth. In April 2020 he abandoned the role of Minister of Justice, accusing Bolsonaro of using his power to prevent his friends from being investigated by the Federal Police. Moro started to build his campaign zeroing in on corruption, but the heat fire from both Lula and Bolsonaro supporters was too much for his candidature to proceed. The accusations from both sides are somehow related to the same facts, the left accusing him of being a corrupt judge working for Bolsonaro and the right accusing him of treason against Bolsonaro.

It’s important to understand those accusations because they relate to an important fact: Lula and Bolsonaro have, at the same time, the largest pooling numbers in terms of voting intentions and in terms of personal rejection.

The 2022 Elections: different speeches, common friends, and a shared silence

Besides the apparent differences between Lula and Bolsonaro, one may be surprised by the things they have in common. The first and most important one is friendships. A staggering 39% of ex-members of the Workers Party occupied positions of power in Bolsonaro’s government. The Ministry of External Affairs has six ex-members of the Workers Party, and even Bolsonaro’s ex-Chancellor of Brazil, Ernesto Araújo, defended Lula’s International Politics in the past.

Regarding the economy, things get even more entangled as both Lula and Bolsonaro pledge support to Agro Business and Industry. Also, both designated bankers for the Ministry of Economy, the difference here is that while Lula will try to use the ministry to reach the industry leaders and farmers (with the traditional subsidies), Bolsonaro uses the Ministry to reach the financial elites (as in the episode where the government allowed banks to take the Emergential Aid as a guarantee in loans). Looking at the people Bolsonaro and Lula surround themselves with. Polarization seems more about narrative and less about the State structures. And yet, both picture the other as the embodiment of all evils.

An essentialist campaign

Another similarity is that Both Lula and Bolsonaro share a surprising campaign abandonment of economic policy. This silence comes from two sources. The first is that nearly all their efforts have concentrated on essentialist issues, a dangerously explicit soul-searching on the true nature of Brazil. This has emphasized their views on racial and gender relations, LGBT rights, the right to self-expression, and the role of the State regarding civil society. Since the beginning of Bolsonaro’s government, two decades of growing polarization started to transform into political violence in several cases around the country. As the cases have increased in number during the last days before the election, they seem to reaffirm the polarization but also work in favor of Lula’s discourse.

The second source of the campaign’s silence regarding the economy comes from the fact that both, Bolsonaro and Lula, allied with similar sectors of the economy and could not promise radical changes. If Bolsonaro, at the beginning of his government, was against financial aid for underserved people, now he is proud that his government improved the old Bolsa Familia by increasing the amount of money each family receives. If Lula was, one year ago, shouting about undoing all reforms conducted by Michel Temer and Bolsonaro, now he is inviting the industry leaders and the financial market to sit at the table to rebuild the country.

The main difference between them, in terms of strategy, is that Bolsonaro cannot escape the radicalization of his political group, while Bolsonaro’s campaign is about warning the nation against the dangers of bringing the Worker’s Party to the presidency again, Lula is inviting leaders to discuss their role in the new government. This fact is reflected in the way they built their alliances. While Bolsonaro reaffirmed the purity of his political group, Lula brought his ex-rival Alckimin, who, during his government in Sao Paulo, was accused of the same things the left today accuses Bolsonaro.

What is at stake?

All in all, what is really at stake now is Bolsonaro`s willingness to get the country back to what it looked like in the ’70s regarding moral politics and power distribution between economic sectors. Lula, on the other side, is not promising anything besides ending Bolsonaro’s agenda.

After polarization has consolidated at the center of Brazilian politics, the 2022 election now underway is not about what the next president will do but rather what their bases will allow them to. During his presidency, Lula was accused of tolerating corruption and silencing every critic of his government with the accusation of “alignment with the dark international forces of capitalism.” Bolsonaro, on the other hand, is accused of promoting violence in all forms and using the State as his personal family office. On Sunday, he still outperformed estimates with 43,3% of the votes. Lula got 48,3% instead. The difference shows that Lula benefited from a campaign centered almost exclusively on the personality of his rival. Still, at the same time, the lack of agreement with Ciro has cost him the possibility of defeating Bolsonaro in the first turn.

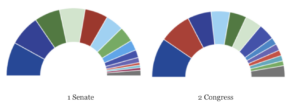

Bolsonaro cannot un-radicalize his base, so he does not have space to grow without hurting his campaign. With Lula, the case is the opposite; in the second round, the supporters of both Ciro and Tebet will turn to Lula. But this doesn’t mean automatic victory for Lula because Bolsonaro’s Party (Liberal Party) won a big chunk of the Congress and the Senate, as did Lula and his allies. The results of the legislative branch show that there are now two polarizations, one between Lula and Bolsonaro and another one between the two of them and the rest of the parties. The graphs below show that Lula’s allies (red) and Bolsonaro’s allies (dark blue) performed well for both Senate (1) and Congress (2), but so did the center (green, light green, and purple).

All estimates for the second round of the 2022 elections point to Lula as the winner. As they have focused mainly on defeating each other, the next president will have a blank check signed by Brazilians under the fear of the opposite side. The real choice now is not about what the country’s future should look like but about what kind of conversation will define it.

Marcelo Silva is a Brazilian researcher, he holds a Ph.D. in Institutional Analysis and a Master in Theory of Justice from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the CGI or its contributors. The designations employed in this publication and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CGI concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers.