Demographic trends in the 21st century

19/03/2021

Author: Daniel Llorente

Demography is one of the most accurate social sciences. In 2021 we know how many adults will enter the labor force in 2039: they have all been born. We also know how many of the current workers will remain active in 50 years: none. This certainty allows us to know exactly what the labor market will be like in the coming decades. We do not need simulations or hypotheses with an uncertain degree of error. Only by obtaining data from civil registries, accurate enough in most countries, we can outline the population pyramid in the near future. There is little interpretive margin. Phenomena such as a pandemic, a world war between nuclear powers, or serious changes in the world food chain would alter these predictions. But without extraordinary alterations, demographics can make long-term predictions with unusual robustness in the social sciences. The data is clear: the world is at a turning point. The demographic future has no likeness in history. And without references, we delve into a reality that is already here: a world of inverted population pyramids. More adults than children. More inactive people than workers. More demand than supply. In this scenario, countries in demographic recession are facing a collapse of their pension systems, inflation, and high migratory pressures. Let us unpack it.

Demographics in the 21st Century

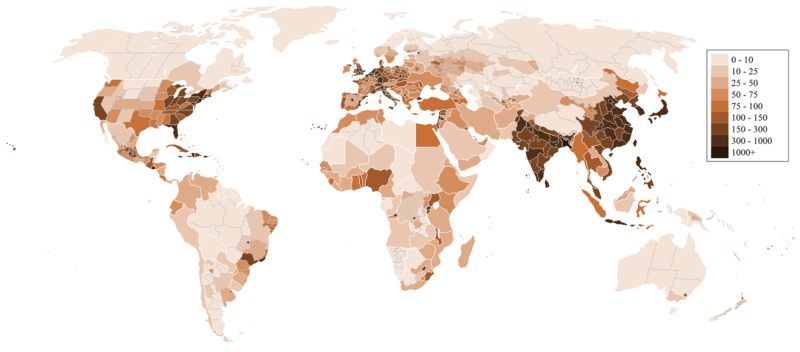

Today we are 7,900 Million on planet Earth. Every day we add about 350,000 babies, but we subtract half of them, who die mainly of coronary and respiratory diseases. Thus, in 2020 the world has gained 1.05% of people, a total of 81M people. With this fast pace, the United Nations expects to reach 10 billion people by 2057, to then moderate the growth to a maximum of 11.5 MM by the turn of the century. In 300 years we will have gone from 1 to 11 billion people. Predictions show we will stabilize around this figure in the next century. Naturally, the world density is very uneven. Together, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and India account for 35.8% of the total population in just 2.5% of the land surface. But it is not these countries that hold the density record. Bangladesh (1,265 p / km2) and Taiwan (673 p / km2) do. At the other end are Greenland and Mongolia (<1 p / km2), with Namibia and Australia 3rd and 4th (<4 p / km2). Humanity prefers the Northern Temperate Zone and the fertility of the river plains of the Ganges, the Indus, and the Yangtze.

Density by countries at 2020

Credit: Junuxx at en.wikipedia [CC-BY-SA-3.0 or GFDL], via Wikimedia Commons

If population growth is vigorous, where does the media noise about “the twilight of humanity” come from. To understand it, we should delve into two concepts: relative growth and total fertility rate (TFR). The first value gives us an idea of the relative growth rate of the population. The second measures the average number of children a woman will have in her reproductive life with current fertility data.

Population growth in relative terms has slowed steadily since 1969, when the population grew by 2.09% annually. It was in this context that neo-Malthusianism was born, a current of thought that foresaw the collapse of food resources. The Green Revolution in India, the one-child policy in the PRC, and the changing trend of TFR worldwide have disproved its frightening predictions, to the point that these theories have today been abandoned and the contrary predictions are being made, on demographic winter.

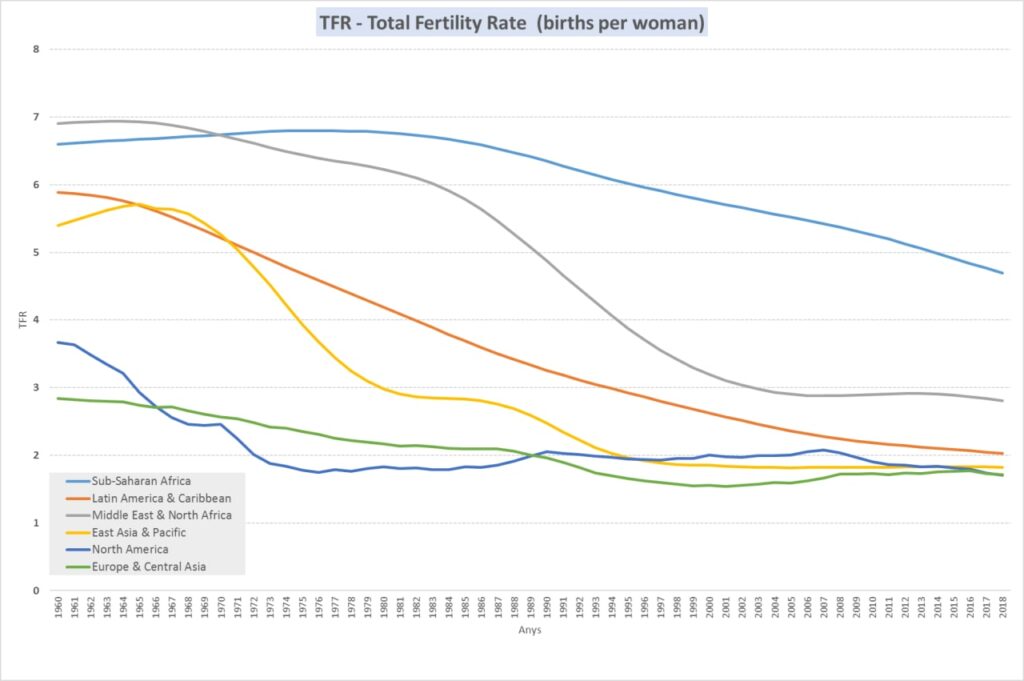

The most interesting phenomenon is the drop in the average number of children per woman, the TFR. In four decades, the global TFR has dropped from five children per woman to 2.4 by 2020, very close to the natural replacement rate of 2.1 below which populations decline. UNSTATS estimates that we will reach this figure in 2063. This is probably an optimistic date, as all revisions of this model have been downward.

Falling fertility is known as the Demographic Transition. There are five stages. From the initial one in a pre-industrial phase, with high birth rates and high mortality to the last one, in a post-industrial world with birth rates well below replacement. During the second-third stage, infant mortality decreases and average life expectancy is extended (especially due to hygienic improvements and caloric consumption) and ultimately the TFR falls and aging skyrockets. This transition is now happening ever faster. If the UK needed 95 years to complete it, countries like Iran or the PRC have completed it in a decade. It is also a global phenomenon. It affects all continents and regions without exception, even in Sub-Saharan Africa, the slowest region to transition, but which is already clearly in the third phase of the transition (TFR of 4.69).

TFR. Past and projections according to United Nations data

Credit: https://ourworldindata.org/

Mortality usually falls before birth does, but when the TFR pay drops below 3 children per woman, the demographic pyramid becomes rectangular and is eventually reversed. During this process, there is a period where the adult population has to care for very few elderly or children, and therefore can invest more time into their careers (assuming that their society generates opportunities). The demographic transition causes an unexpected bonus: the demographic dividend.

This demographic structure generates a temporary peak in the working age population which, if well managed, tends to generate great advances in per capita income and welfare. All of Western Europe and the United States benefited from their transitions in the 60s and 70s, after the peak of post-World War II births (the Boomer generation). Japan in the 60s and 70s also reaped its benefits, as China and South Korea did more recently. Now many countries in Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Bangladesh) are growing rapidly, driven by a reduction in their dependency rate. Even the Soviet Union benefited from it in the 1960s, after the demographic cataclysm of World War II, when 8.9 million Soviet citizens died. In contrast, regions such as West Africa, the Maghreb, Brazil, and South Africa are not taking advantage. Nor do many Caribbean states (Cuba, Venezuela, Honduras). Chile and Costa Rica are making progress, with TFR already fully comparable to that of the West. Although productivity plays a role, there is a clear correlation between the percentage of active population and GDP growth. Unfortunately, the demographic dividend is temporary. Slowly but inevitably, these abundant cohorts become seniors, emerge from the productive fabric, and begin to make intensive use of the social protection (pensions, health) that the younger generations have to fund.

The literature on the causes of falling birth rates is extensive [11]. There is a large constellation of situations that matter in the decision to have children. In the developing world, the key factor is being able to decide the adequate number. With access to education and paid work the control that women have over their own lives grows. In developed economies, the low birth rate is due mostly to socioeconomic causes. Endemic unemployment and high educational requirements to enter the labor market cause a delay in emancipation. This translates into a reduction in the number of children, as the reproductive age range has a biological limit. In many of these countries, the difference between the desired ideal family size and the actual TFR is growing year after year. Many women cannot have all the children they would like due to the complexity of the labor market, the lack of state support, the opportunity cost of having a child in the leisure society, and the growing cost involved. In countries with lower per capita income, the least advantaged are those who have more children, in affluent societies, it is the other way around.

There are three social phenomena linked to aging that need to be taken into account to better imagine the world to come. Growing urbanization (and rural depopulation), falling worker-dependent ratios, and resistance to political change stemming from increased political power by seniors, usually more conservatives.

It should also be added that global demographic weakening could, counterintuitively, increase demographic currents. Emigrating is expensive and hence it is usually the middle-income groups that start the process in most societies. It is a complex mechanism, but so far it has followed a clear pattern: when a country that is less advanced in the demographic transition increases its income, economic inequalities between world regions encourage emigration. With more resources, more communities can afford to send their young people on the adventure of the American or European dream (but not Chinese or Japanese, more reluctant to accept it).

The countries that are more advanced in their demographic transitions face enormous pressures derived from this. If their governments choose to encourage immigration, the weakening of the central ethnic core of the state may weaken internal cohesion and lead to an increase in xenophobic populism, as well as the creation of unassimilated groups. But if borders remain closed and low birth rates are not offset by immigration, states like Japan and Russia (in a first phase) and China or Iran later could lose geopolitical positions with respect to their historical opponents, with better demographics. If this remains the case, large regions of the world would be depopulated, such as the Amur basin or the plains of Eastern Europe. At the same time, other regions would emerge from the darkness and become vibrant metropolises, such as the Congo River Basin (Kinshasa-Brazaville) or the Gulf Coast of Nigeria (from Abidjan to Lagos, via Accra).

The economic implications of aging

Are there too many people or too few? If we fit the entire world population into a territory with the density of Barcelona (15,992 p / km2), the 11.5M foreseen for 2100 could live in Chile (750k km2) and there would still be plenty of space. The rest of the world would be a large natural and agricultural park. Is the Earth too small then? It does not seem so, and if it were, by the XXII and XXIII centuries we should be able to migrate to other rocky bodies in the Solar System. But in the midst of the biodiversity and climate crises, many see the decline in the birth rate as a good thing. Fewer humans, less pressure on the environment. A welcomed change? From an economic point of view, the answer is no.

Contrary to predictions of collapse, the sustained rise of humanity has generated technological and welfare progress. It is a proven reality. All indicators of human development have improved over the centuries, especially after the industrial revolution. Longevity, access to education, elimination of hunger, access to drinking water, and poverty reduction. The world has made a large leap forward since the 17th century when Thomas Hobbes described life outside society as ‘nasty, brutish and short’. A description that fitted the life experience of most of his contemporaries. The improvement in human development has been especially rapid over the past thirty years, with the integration of East and Southeast Asia into the World Economy. We call it Globalization. The increasingly interconnected -and therefore more efficient- human workforce has made this possible. In the past, only wars and pandemics have stopped the exponential growth of human societies. And now for the first time in history, we are preparing to abandon this well-known paradigm and entering a new one: the demographic recession.

Before the stage of demographic recession, we are currently facing the problem of inverted population pyramids. The original pyramid becomes a monolith where all the cohorts have similar sizes. We are in the “hot spot”, where the economic benefits the most of the worker-dependent ratio: few grandparents, few children, and many adults in the 18-65 age group. Bur progressively, workers are retiring and smaller youth cohorts are insufficient to replace them. The contribution-to-retiree ratio is beginning to rise [14] and immigration is unable to make up for the deficit.

This creates tensions that are difficult for any government to overcome. Pension systems are becoming unsustainable and spending is rising. This translates, ultimately, to the dismantling of welfare systems. Governments know that, politically, this is a suicide, because an increasing number of people depend on pensions as their main source of income. In many societies, up to 30% of the electorate may vote depending on pensions. And it is not a problem of democracies alone. Putin’s Russia had to withdraw a reform of the pension system in 2019 due to the strong popular contestation.

The first solution that most governments try is to compensate the spending with unbalanced budgets. In countries with fiscal margins, this can work well, especially if the economy continues to grow. Others will try to cover the deficit via sovereign debt issuance. This is a path that countries with debts of less than 70% of their GDP can take, as some 2 to 4 extra points of the yearly deficit would bring these economies to 130% by 2050. Traditionally, this is the debt limit of what is considered sustainable. Only Japan or Italy, with debt markets dominated by local buyers, have been able to sustain high levels of debt in the long run. There is a third group of countries that already in 2020 are above 100% of sovereign debt with respect to the size of their economy. Besides the aforementioned. Greece, Spain, Portugal, and Belgium are some of the most indebted countries. This group also suffers from the worst demographics in the world, all of them with TFRs clearly below 1.5. These two conditions compound with each other to create a truly stark economic future.

The growth of indebtedness is linked to that of the economy. If every year the deficit and GDP increase by 2%, the relative increase in debt is zero. In a scenario of a demographic crisis, the structural growth of GDP is moderate or even negative. This can skyrocket the public deficit. If countries do not find domestic resources in the form of savings to wipe it out, they must borrow in the international financial markets, which react by raising the risk premium. In the past, central banks have intervened to moderate interest rates via purchases in the secondary sovereign debt market (the money-making machine). This intervention, now often called quantitative easing, is expected to be reduced in the medium term, especially if inflation rises. For example, the European Central Bank buys 20 billion euros a month in sovereign debt. It is not credible that this mechanism could be increased to solve future state treasury crises.

And that brings us to the endpoint of this analysis. Inflation. In recent years we have enjoyed a long period of moderate growth with even negative inflation (deflation). There is a neverending amount of debate amongst economists about the reasons for this era of low inflation. One of the few consensus points is that China’s entry into global production chains has contributed most to this, followed by wage moderation and rising productivity in the West. This situation is exceptional. In the twentieth century, the main task of Central Banks was to fight major inflationary crises (especially arising from the oil crises of the 1970s).

In a future with demographic decline, Europe and East Asia may witness a triple inflationary shock. The first shock comes from the reduction in the share of the population in working-age. Employed adults not only generate GDP and pay taxes, but they also save more than they consume. They are a deflationary force. Dependents not only do not produce, but they consume and have negative savings rates. They are inflationary.

The second shock comes from the end of the largest population movement in history: China’s internal migration from rural inland to coastal manufacturing areas. The influx of (poorly paid) workers into the workshops in Guangdong and the Yellow River Delta has been highly deflationary. Hundreds of millions of workers have joined the global industrial effort. Furthermore, these workers have traditionally saved a good share of their income. These savings have flown to the West in the form of the purchase of sovereign debt by the Central Bank of China, which in 2020 accumulates 3.21 trillion in foreign currency. This is over. In 2017 and for the first time in history, China’s labor force began to shrink (from a high of 776 million). Soon the PRC will have to repatriate investments to meet the needs of its aging population. This will make capital more expensive in the West and hamper the work of the Federal Reserve, which has so far kept the US economy stable despite the US government’s high deficit. We will see if the Dollar’s “Exorbitant Privilege” remains in place since it was established as the world’s reserve currency in Bretton Woods in 1944.

And the third shock may come from salaries. The Western and Asian working masses, so far deprived of their bargaining power by East Asian labor competition, could see their power regained. In a scenario of a shortage of young and trained staff, unemployment would fall and, in return, wages and inflation would rise. This relationship is the well-known Phillips curve. The sectors most prone to generate wage increases will be those related to health and care for dependents, not prone to automation and increases in productivity. Other sectors could perhaps explore the Indian and African subcontinents to replicate the offshoring of East Asia. This is problematic, as it is not clear that the labor culture and political stability of these regions will allow them to replicate the disciplined industrialization of the Asian Tigers.

It is not clear how central banks will resolve an inflationary scenario in countries already saturated with public debt. On the one side, if reference rates rise they will cause a sovereign debt crisis and cascading bankruptcies in the financial system. On the other side, if they keep them at the current historically low levels, the crisis will be one of inflation. This could place many companies in a scenario reminiscent of the 70s of the twentieth century: interests above 10%, depreciation of savings, and even strong industrial reconversions.

We will probably witness the latter.

Daniel Llorente is a computer scientist working at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland. He holds a doctorate in electronic engineering from the Technical University of Munich.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the CGI or its contributors. The designations employed in this publication and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CGI concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers.