Cape Independence: The Return of History to South Africa

04/04/2023

South Africa has become immortalized in the collective memory of the Western world through a narrative of heroism and hope molded by the socio-political circumstances of the 1990s. The South Africa that most people know is one of Nelson Mandela, the defeat of Apartheid, and the promise of an exciting future guided by justice, courage, and opportunity. The gradual increase in South Africa’s obscurity to most in the West since 1994 can perhaps best be symbolized in the craze that erupted upon Mandela’s passing in 2013, in which vast numbers of people reported their belief that he had already been long dead.

Despite a sense of collective disinterest that has pervaded the West’s attitude toward South Africa over the last two decades, the passage of history has not lessened its pace in the country. In fact, some of this disinterest may actually serve as a response to discomfort. Unlike the future history presumed by the triumphalism of the 1990s, the reality of post-Apartheid South Africa has proven disappointing and, in many ways, unsettling.

Mandela’s unfulfilled dream

Not long after the departure of Mandela from South Africa’s political landscape, the country became embroiled in now long-standing issues with corruption, economic mismanagement, staggering crime rates, ethnic unrest, eroding infrastructure, and a general sense of incompetence of its leadership. Millions of South Africans have emigrated during the past three decades, and it remains far more likely for a South African to be murdered than to die in a car accident, despite the country also sporting one of the highest numbers of road deaths in the world. The political class that has succeeded Mandela has put the nation to shame, generating scandals like the alleged rape by former President Jacob Zuma of his family friend’s HIV-positive daughter, along with a dizzying number of corruption charges that ultimately landed the former president behind bars. This came all the while rising unemployment eventually reached around half of South Africa’s under-35s by 2021, contributing to devastating riots initiated by Zuma’s supporters following his imprisonment, leaving hundreds dead and constituting the worst violence the country has seen in the post-Apartheid era. South Africa’s latest crisis has materialized in the unbelievable realization of its governing elite to forsake the surplus of cheap energy available a few decades ago for constant and worsening nationwide electrical blackouts today.

The country’s increasing distress has, to some extent, translated to the polls. South Africa is awaiting a general election that will take place next year, and a preliminary study of voter intentions has indicated that there is a very real chance of 2024 marking the first time in two decades that Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) will fail to reach 50% of the vote and will have to negotiate a coalition government. While the ANC may opt to partner with the liberal Democratic Alliance (DA), a more radical option may come in the form of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF). The latter is an openly Marxist-Leninist movement founded in 2013 which promises to expropriate white-owned farmland without compensation, officially endorses Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and celebrates China as “the torch-bearer for all Marxist-Leninist formations in the world.” Moreover, the party and its leader, Julius Malema, have been repeatedly accused of making racist remarks against Indians and White South Africans while fermenting a vengeful form of Black nationalism. Malema’s rejection of the inclusive norms that defined Mandela’s approach may be seen as part of the larger global trend of populist nativism in the 21st century, threatening to upend the liberal post-Cold War world order.

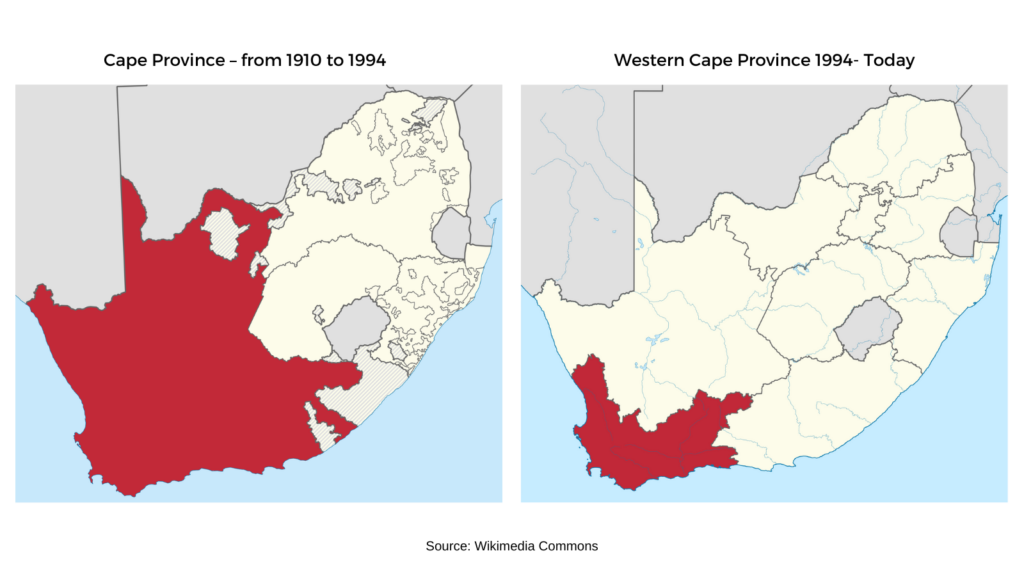

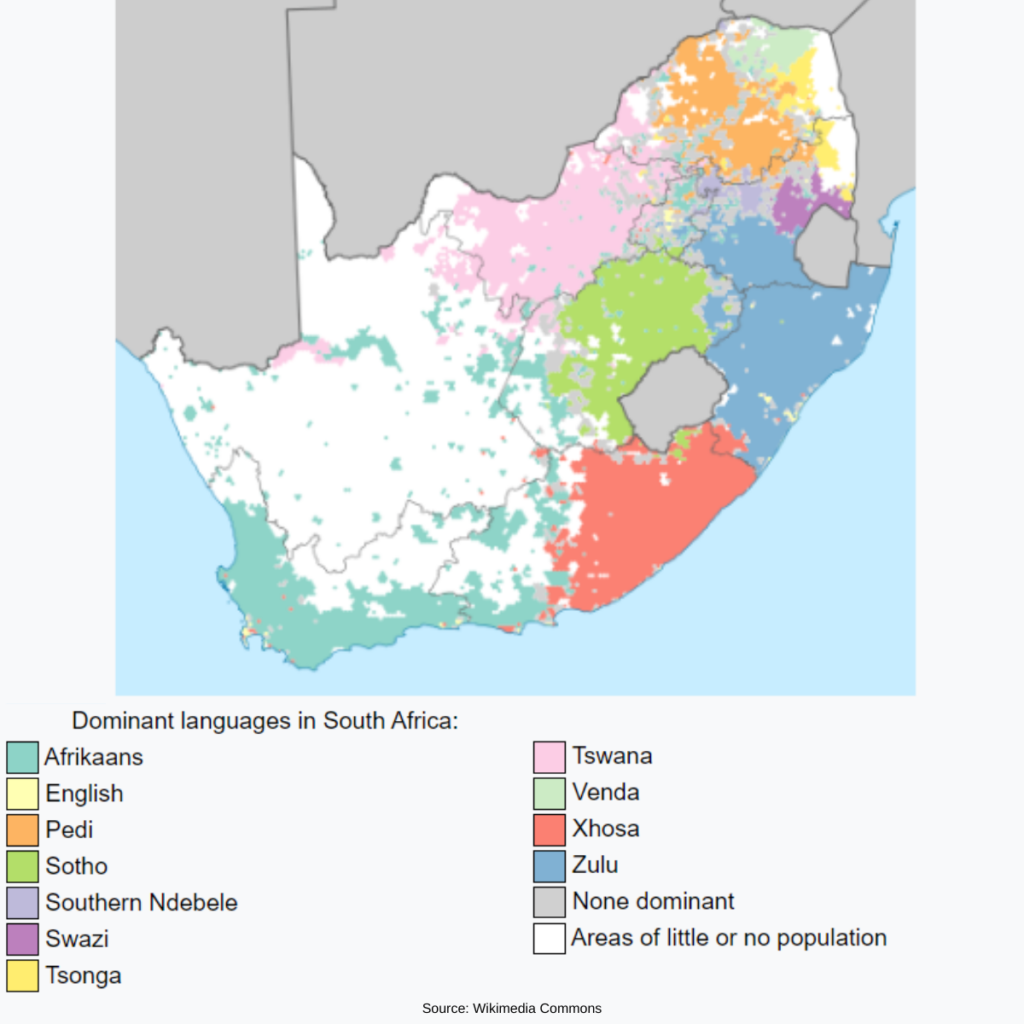

Malema’s movement is of particular concern for many in South Africa’s Western Cape province, a region whose fortunes have somewhat differed from the fate consuming the rest of the country. The Western Cape is often considered the most well-governed province of South Africa, and it is no coincidence that it is also the province that has voted most consistently against the ANC. It was the only province to vote for the National Party instead of the ANC in 1994, and since 2009 residents of the Western Cape have been the only ones to repeatedly vote for the DA. This political divergence has a long history in the region, which was also the first part of the country to be settled by Europeans. Moreover, until 1956, the Cape served as the only region in South Africa where non-White populations retained suffrage, and was home to South Africa’s most prominent liberal party and parliamentary force against Apartheid – the Democratic Party.

The overwhelming national dominance of the ANC over the past three decades has increasingly frustrated the voters of the Cape, and the fragility of South Africa’s commitment to pluralistic and multiethnic democracy that has been exposed by the EFF’s success has only worsened anxieties in liberal-minded Cape Town. However, these challenges are proving to be catalysts for creative thinking, as political developments in the Cape are beginning to signal serious consideration for something maybe even more radical than the EFF’s party platform. Namely, many are coming to engage in the prospect of the Western Cape’s secession from South Africa.

The case for the Western Cape’s secession

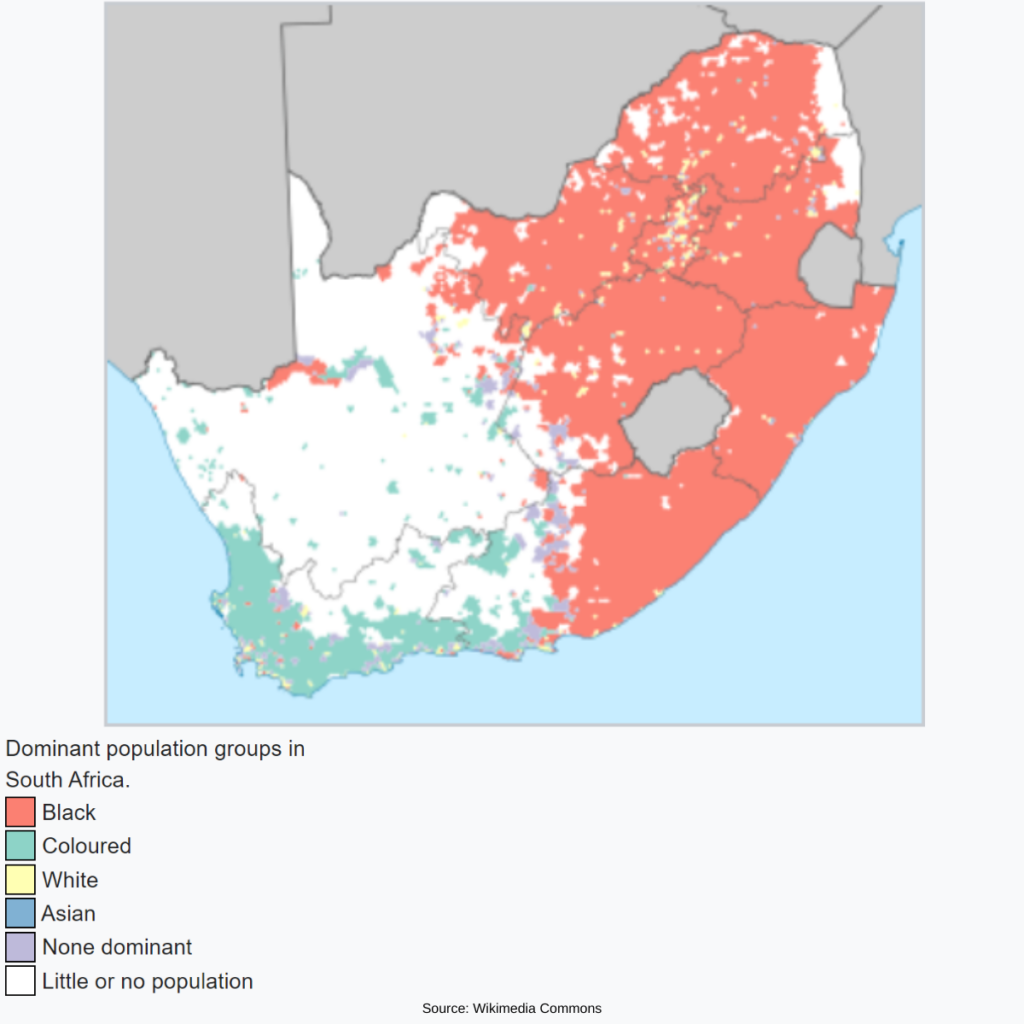

Initially, many in the country laughed at the concept, but the passage of time has revealed a significant increase in its popularity. For example, a 2021 poll made the headlines after demonstrating that a majority of the province’s population was in favor of holding a referendum on secession. Moreover, this brought about the creation of the Western Cape Devolution Working Group in September of last year, which brings together the region’s largest political force—the DA—with organizations overtly promoting Cape independence, and aims for the devolution of powers away from South Africa’s national government. Numerous organizations have emerged that capitalize on and bolster this sentiment, including the Cape Independence Advocacy Group, the Cape Independence Party, the Cape Coloured Congress, CapeXit, Gatvol Capetonian, and the Sovereign State of Good Hope. Notably, two of these organizations (the Cape Coloured Congress and Gatvol Capetonian) aim specifically to promote the rights of South Africa’s mixed race population, known as Coloureds, and one organization (the Sovereign State of Good Hope) is linked with the interests of the ethnic Khoisan, a unique native ethnicity of non-Bantu origin. This consolidation of support from national ethnic minorities with strong bases in the Cape forms the core of the movement’s flavor, especially given that Coloureds constitute the largest single ethnic group in the Western Cape, at around half of the population. Arguably the largest victory of this kind, however, came in the form of the official pledge of support for Cape independence in late 2020 by the Freedom Front Plus, the largest and most successful party endorsing attention to South Africa’s Afrikaans-speaking population.

Interest among these various minority groups in Cape independence is quite rational given policies implemented by the ANC over its three decades of rule. The most frequently cited policies Cape independence advocates promise to abandon include race-based legislation implemented by the ANC. Over the years this settled into forms like Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE), which restricted all companies that were not 51% Black-owned from entering into bids for government contracts, and legislation implementing racial quota systems for employment and housing priorities. While Coloureds are often meant to be considered “Black” for the purposes of these kinds of legislation, many feel these systems are discriminatory toward them in practice. Many Coloureds have also expressed anxiety toward cultural shifts and labor market competition resulting from internal migration to the Cape. This is particularly pronounced in the rhetoric of Gatvol Capetonian, but was also at the heart of a scandal in the South African parliament in March of this year, in which Peter Marais, a Coloured representative in the Western Cape Provincial Parliament, referred to the ANC as “foreigners” to the region.

Marais is also a member of the Freedom Front Plus, and a native speaker of Afrikaans, which is no coincidence. Most Coloureds in South Africa speak Afrikaans, as does around half of the population of the Cape. This is at the core of interest toward the movement by Freedom Front Plus, which has been increasingly aiming to attract Coloureds into its party, and which has celebrated the idea of an independent Western Cape “where Afrikaans can take its rightful place as the language of the majority.” Jack Miller, leader of the Cape Independence Party, has also referred to Afrikaans as the Cape’s “majority language,” and appears to base his ideal borders of an independent Cape on the geographic reach of Afrikaans-speaking municipalities.

Ultimately, it is the numerically superior Afrikaans-speaking Coloureds who form the true backbone of the Cape independence movement. However, relatively high levels of support for Cape independence among White South Africans has led some to call the movement “nostalgia for the Boer republics” or to suggest that it is implicitly pushed by racist sentiments. This is not helped by the legacy of interest in the idea of a separate state for Afrikaans-speaking Whites, commonly referred to as the Volkstaat, after the end of Apartheid. However, the reality of the Cape independence movement reveals a more complex transformation that has taken place over the decades, most notably in the form of a growing alliance between Afrikaans-speaking peoples of all ethnic backgrounds, flavored with a classical liberalism traditionally associated with Anglophone South Africans and the Western Cape, and united in the defense of non-racialism and merit-based policies. This powerful blend may also achieve far greater success than other regionalist movements, such as the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party, thanks to finance: throughout the whole nation, only the Western Cape and the highly urbanized Gauteng province generate net contributions to the national budget. The proliferation of narratives around financial independence and administrative superiority thus renders secessionist sentiment in the Western Cape relatively similar to that of Catalonia.

However, the fate of the Cape’s secession process may also parallel that of Catalonia’s. The South African government is very unlikely to accept any attempt by their second wealthiest province, and possibly up to half of South Africa’s territory, from breaking away. Moreover, there are scant legal obligations for the South African government to respect such initiatives, and some have already referred to the movement as “treasonous.” However, the incentives pushing the movement forward are strong, and will only gain in momentum as South Africa faces increasing political and economic instability. If the movement continues to be ignored by the national government, supporters have claimed they will call on the international community to take action, or even declare a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) after securing power in local government. This is when things could get ugly, and when a sense of shock might ripple across the whole Western world as the failure of Mandela’s dream of an enlightened, liberal, and multiethnic South Africa becomes irrevocably clear.

The Cape independence movement in a postliberal global context

In many ways, the push for Cape independence is part of a reaction to the global decline of liberal democracy and its values over the past decade, and as such, a crisis generated by the movement would likely elicit an especially strong impact on political discussions in North America and Europe. In some ways, this may prove reminiscent of the war in Ukraine, as a serious geopolitical crisis would emerge in a nation that is considered to be fairly close to the larger Western world, and one grappling with some of the same socio-political debates. However, in many ways South Africa is closer to the West, and especially the Anglosphere, than Ukraine. This proximity is especially apparent in South Africa’s debates around “wokeness,” political correctness, and particularly divisive racial identity politics, perhaps best encapsulated in former DA leader Helen Zille’s best-selling 2021 book Stay Woke, Go Broke: Why South Africa Won’t Survive America’s Culture Wars. A collapse of South Africa, manifested by the Cape’s secession, would certainly constitute an uncomfortable reality for many in the West to come to terms with, and the event would very likely find itself at the center of the same foreign culture wars currently inflaming South Africa’s tensions today.

In speaking of culture war, it must be noted there remains a non-zero chance for the Cape independence movement to attract the attention of Elon Musk. Musk is arguably the most influential South African alive today, custodian of what is perhaps the world’s most politically influential social media site, and a polarizing public figure whose known political sympathies signal potential support for the movement. Any kind of engagement on his part with the Cape independence movement would be groundbreaking, as it would likely constitute Musk’s greatest level of engagement with South Africa in decades, and could also serve as a vital, but potentially divisive, part of the Cape’s strategy to garner international support. The war in Ukraine has demonstrated that resolute public narratives and concentrated activity on social media, especially in the form of Twitter, can be extremely valuable in establishing legitimacy.

On balance, the Cape independence movement is more likely to garner support from right-leaning actors in the West, a relatively unique trait compared to the traditionally left-leaning secessionist movements of Catalonia, Scotland, or Québec. However, public sympathy may also emerge downstream of geopolitics, and it is through geopolitical realism that Cape independence may find its greatest opportunity for success. South Africa served as a steadfast, brutally efficient, and controversial American ally during the Cold War; but in the post-Apartheid era, the country’s ANC government has increasingly cozied up to America’s rivals. This can be witnessed in the ANC’s questionable UN voting record, prolific engagement with Chinese investment, and participation in military exercises with China and Russia during the one-year anniversary of Ukraine’s invasion. Pretoria has also declined to participate in the planned “Cutlass Express” military exercises with the US this year, leading many in Washington to come to the conclusion that “Pretoria is no longer non-aligned … they have chosen Russia’s side.” Some American policymakers have also expressed concern toward “consistent interparty cooperation” between the ANC and the Chinese Communist Party. This is accentuated by statements in the ANC’s National General Council (NGC) 2015 discussion document, which praises “the exemplary role of the collective leadership of the Communist Party of China,” arguing that it “should be a guiding lodestar of our own struggle,” and that Beijing “has heralded a new dawn of hope for further possibilities of a new world order.” Given this trajectory, there is a growing potential to argue that support for an independent Cape may be in the strategic interest of the United States.

This is perhaps the most globally significant aspect of the network of incentives pushing the Cape independence movement forward. It was always inevitable that increasing corruption, crime, racial tensions, energy blackouts, unemployment, and economic stagnation under ANC rule would eventually awaken the consciousness of a politically, linguistically, and ethnically distinct population in South Africa’s Cape region. While it is impossible to say when this consciousness will become impossible to ignore for South Africa’s political elites, there is a real potential for this movement to have a significant impact on both a domestic and global scale. There is also a very real threat of danger ahead for Cape independence supporters, as Catalonia’s experience has already demonstrated the unlikelihood of an EU and NATO member state entertaining secession peacefully, and the chance of this in South Africa is even less optimistic. However, danger also lies ahead for the world at large in the 21st century, as great powers return to competitive behavior in the international arena. This is both a blessing and a curse, as a healthy dose of geopolitical realism elucidates that securing US support is truly the Cape’s best shot at pronouncing its self-determination. While sympathy is far more likely to emerge from America’s Republican Party, which has demonstrated greater displeasure toward the ANC’s governance, the Cape independence movement should make their case as non-partisan as possible when aiming to secure US support. Violence is not inevitable for the Cape independence movement to succeed, but it is vital for the movement to surround itself with powerful friends if it wishes to be taken seriously. Gaining the patronage of a global power contends to be one of the only ways the ANC might be forced to accept the results of a referendum.

If anything is certain, it is that history is far from over in South Africa, and the success or failure to secure an independent Cape will prove to be a lesson for all secessionist movements that find themselves in the emerging 21st century landscape of geopolitical competition.

Sven Etienne Peterson is a freelance writer and graduate student at the University of Glasgow, University of Tartu, and the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the CGI or its contributors. The designations employed in this publication and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CGI concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers.